Voices:FAMSF: Testing a new model of interpretive technology at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Catherine Girardeau, Earprint Productions, USA, Alexa Beaman, Guidekick , USA, Sheila Pressley, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, USA, Jason Reinier, Earprint Immersive, Inc, USA

Abstract

In this paper, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) and Earprint Productions discuss how a mobile app that enhances visitor learning and engagement in a museum setting—Voices:FAMSF—can also position visitors as co-creators of their museum experiences. It shows how the app correlates—in design, content, and functionality—with trending museum educational practices that give visitors agency over, and a voice in, their learning in a museum setting. Thus, visitors are able to choose how, when, and where they will experience educational content and participate in the interpretive process. The paper also discusses why FAMSF chose an open-source framework to build Voices:FAMSF, and how museums benefit from open-source development. FAMSF came to Earprint Productions with a challenge: use mobile technology in new ways to enhance, rather than detract from, the very experience of being in the presence of great art. The solution Earprint and the Museums arrived at is an immersive soundscape app, Voices:FAMSF, that interprets key outdoor sculptures and architecture at both the de Young and the Legion of Honor. The app is location sensitive (audio content is driven by the viewer’s location via GPS), customizable (viewers choose to hear their own “mix” of museum voices, community voices, or both), and participatory (it allows visitors to co-create content by recording comments in response to museum-curated prompts).Keywords: mobile, apps, locative, crowd-sourced, soundscape, visitor-centered

1. Rethinking facilitated experiences at the museum

by Sheila Pressley

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (or FAMSF, pronounced Fam. S.F.) comprises the de Young and the Legion of Honor museums. As a museum educator at FAMSF for thirty years, my goals for those visitors who want a facilitated experience in the galleries is for them to visually engage with works of art, learn from specialists, and contribute to an ongoing dialogue about the art. The most utilized means of interpretation at both of our Museums is the traditional audio tour; over 86,000 visitors rented an audio tour at the Museums last year. Audio tours are useful because they are readily available and provide access to knowledgeable curators and experts. I appreciate that a straight audio tour does not hinder visual engagement with the art. The obvious drawbacks to the audio tour are these: they are usually rented for a fee; the content and artworks selected cannot be modified for visitors’ preferences; and, of course, visitors can’t engage in conversation or ask questions about the art.

Our 207 docents continually train and refine their skills in art interpretation and visitor engagement. Docents can provide the voice of the specialist and adjust content to meet the visitors’ specific needs. Docent tours occur at set times and are therefore not available to all visitors. In addition, many visitors do not want to invite a third party into their art experience. Our docents provided guided tours to around 70,000 visitors this past year and did not have the bandwidth to reach those additional 86,000 who rented audio tours, if indeed those visitors had wanted a tour by a third party. However, those 86,000 visitors did clearly want a facilitated experience. (To put these numbers into context, FAMSF had over 1,750,000 visitors last year; less than 1 percent opted for either an audio or docent tour of our temporary exhibitions or permanent collections.)

What is the best way to reach those who want a facilitated experience? How can we take the best of both facilitated methods and create something that could be available to all FAMSF visitors, providing everyone with the option of facilitation? Could we create a model that would be attractive and useful to more than 1 percent of our visitors?

To make a facilitated experience available to more visitors at more times, we chose to rely on the seemingly ubiquitous handheld smartphone. According to the Pew Research Center’s 2013 report, 56 percent of all U.S. adults own a smartphone (Kerr, 2013). The newly published report “A Closer Look at Arts Engagement in California” reports that 40 percent of all Californian adults consume arts through a handheld or mobile device (Novak-Leonard, Wong, & English, 2014). But what is the best smartphone technology to employ? Most museum apps of which I am aware compete with the visual experience of being in front of a work of art by drawing the viewers’ attention to a small screen. I strongly believe that the experience of looking must be prioritized in any facilitated gallery experience.

To devise a new type of interpretive technology for FAMSF, we formed a partnership with Earprint Productions, an award-winning firm specializing in digital storytelling, and Halsey Burgund, a sound artist and software developer internationally renowned for his aural tapestries that incorporate multivalent voices. Together, building upon Burgund’s open source software, called Roundware, we created Voices:FAMSF, a free app downloadable to any device with GPS. A discussion of why we opted to use Roundware follows this section.

What is Voices:FAMSF?

Voices:FAMSF is first and foremost a soundscape. It was designed to create an immersive audio experience that encourages close examination of works of art. Over a track of ambient music are mixed numerous voices, illuminating key points of interest about and suggesting visual highlights of each work of art. These voices discuss twenty-one outdoor sculptures and architectural details at the de Young and the Legion of Honor. We decided to focus on outdoor art and architecture so we could experiment with global positioning. We initially planned to rely on GPS to identify the exact location of each user and supply content specific to each work of art or architectural feature within the immediate area. Our hope was that the GPS would allow participants to seamlessly move from one work of art to the next without having to divert their attention and enter a number on their mobile device. We quickly found that GPS is not accurate enough to adequately identify objects being discussed to users’ satisfaction. We installed outdoor Wi-Fi at both the Legion and the de Young to enhance the GPS, which improved accuracy, but with the close proximity of some works to each other we knew that app users might still experience confusion as to which work of art the audio content related. Before we launched the beta version of the app, we began working on a feature that would enable audio comments to be tagged to images of specific art works. This new feature has not yet been tested; we anticipate that it will diminish confusion but are concerned that our initial desire to keep visitors looking at art and not their mobile devices may be compromised.

Museum curators and other experts provide some of the audio interpretations. We titled these “museum voices.” The museum voice recordings are broken down into thirty- to fifty-second segments and woven into the musical soundtrack. This gives the viewer time to process information and hopefully encourages more time spent looking at and experiencing art. The comments are presented randomly to free visitors from a purely linear, intellectual response to art, and hopefully support a more visual and emotional response. It was important to encourage and validate each user’s personal responses to the art, as that is at the heart of engagement. To do so we took Burgund’s lead and included a track of comments left by museum visitors; these we titled “community voices.” We asked museum visitors to record their thoughts and impressions about the Museums’ outdoor art and architecture. When we began recording community voices, we were impressed and very pleased with the thoughtful quality of comments. These too were edited and interwoven into the soundtrack. App users can personalize the soundtrack; users can select to hear the voices of art professionals, of inquisitive and observant museum visitors, or a mix of both.

Perhaps the most engaging aspect of this app is the invitation Roundware extends to all users of Voices:FAMSF to co-create content and engage in what becomes an ongoing community conversation about art. This combination of voices continues the Museums’ interpretive shift to encouraging art exploration as a conversation with viewers, rather than a lecture from an authoritative expert. All Voices:FAMSF users can record their own twenty-five-second audio comments in response to open-ended prompts. Even if app users decide not to add a recording, we hope that the invitation alone will remind users that the Museums value and encourage each visitor’s thoughts. If users do want to add a comment, the recording interface is simple, and it allows users the opportunity to review their comments before they are added to the soundscape to be played at random in the mix of community voices for future participants. Currently, comments go live immediately and are later reviewed and edited only if they violate acceptable use agreements. We have received some feedback from early testers that they do not want to listen to comments that are not relevant; currently that issue can be resolved by users selecting only museum voices. Other Roundware developers are refining a feature that allows a user to like and vote on the quality of visitor comments. This may be incorporated into Voices:FAMSF at a later date. At this point, we are finding the vast majority of visitor comments to be useful and insightful.

To deepen the experience after the tour, Voices:FAMSF provides the user with access to in-depth interpretations of the art and architecture included in the app, through the online site http://www.famsf.org/about/voices/explore-more. The online experience provides rich text and audio interviews with museum experts. The online portion of Voices:FAMSF is intended to function as either a pre- or post-visit experience. Our primary goal is to encourage interaction with the art while at the Museums.

Voices:FAMSF beta version

We released a beta version of Voices:FAMSF in October 2014. We were anxious to learn whether the app was effective in encouraging visitor engagement and if the concept of a location sensitive, customizable, non-linear soundscape that mixed community voices with professional museum voices was an enjoyable interpretive tool. One early tester told us, “This is not a tour: it is an experience.” We were extremely curious; did our visitors want an experience or a tour? Should additional resources be directed towards the concept of a museum experience? We knew we would be creating a major new audio interpretation of our permanent collections in the near future and wanted to take learnings from Voices:FAMSF and experiment with indoor location detection. We had already begun designing a fix to the problem of inaccurate location detection outside, but we still needed to document other necessary usability refinements. Although we did not have the resources to fund a professional formative evaluation, we were fortunate to find a museum studies’ graduate student willing to conduct a study of the Voices:FAMSF beta test as her thesis project. Beta survey results conclude this paper.

2. Background: Why Roundware?

by Catherine Girardeau and Jason Reinier

The Voices:FAMSF app was built using open-source software called Roundware. Earprint Productions had been interested in creating a project with Roundware since our CEO, Jason Reinier, met Roundware’s creator, musician and sound artist Halsey Burgund, at Museums and the Web in 2010. The right opportunity came along when FAMSF came to Earprint wanting to reinvent the traditional audio tour for their outdoor exhibition spaces. Earprint proposed a soundscape-based app with location-sensing capability, built using Roundware. The collaboration between Earprint, Burgund, and FAMSF resulted in the innovative, participatory soundscape app, Voices:FAMSF, which interprets the outdoor spaces at the de Young and Legion of Honor museums with a mix of ever-evolving museum and visitor commentary and a music bed composed by Jason Reinier.

Burgund originally created Roundware in 2007 for a specific purpose: a commission from the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, ROUND (http://halseyburgund.com/work/round/). He wanted to subvert the traditional audio tour by creating a tour that was bidirectional, inclusive, and participatory. He wanted museum visitors to be able to have asynchronous conversations with other visitors. The name Roundware refers both to King Arthur’s round table, at which all opinions have equal opportunity to be heard, and the musical round, a vocal tapestry in which the voices interweave, overlap, and follow one another.

Roundware is a flexible, distributed framework that collects, stores, organizes, and re-presents audio content. Basically, it lets you collect audio from anyone with a smartphone or Web access, upload it to a central repository along with its metadata, and then filter it and play it back in continuous audio streams.

Burgund wanted his software to be open source because he liked the idea of giving back. He owns Roundware’s official source code but chooses to share it and allow other developers to freely build upon and extend his original creation with the hope that they will contribute back to the whole. There are several benefits to the museum community of using open-source framework like Roundware. The economic upside is that you aren’t married to proprietary software; you can go in and change the code if you want to. The museum benefits from the collective innovations of other Roundware developers, and also contributes its own innovations to a community project. Becoming an early stakeholder in such a project is a win-win—putting the museum on the map not just as an early adopter but also as an innovator—while also contributing to a community project that benefits the museum community as a whole.

Roundware gets deeper and more flexible with each project that builds upon it. After ROUND came SCAPES, another sound artwork at the deCordova Museum (http://www.decordova.org/art/exhibition/platform-3-halsey-burgund-scapes). SCAPES incorporated location sensing, a feature ROUND was too early to take advantage of. Roundware was developed to facilitate creation of sound artworks, but with new users, its application was extended.

When the Smithsonian chose to use Roundware, new features were developed so it could be used for education and interpretation. Stories from Main Street (http://www.storiesfrommainstreet.org) used Roundware to community-source oral histories about life in small-town America, in connection with the Smithsonian Institution’s Travelling Exhibition Service’s Museum on Main Street exhibits. Participants shared stories of small-town America and added them to an audio archive.

The Smithsonian’s next Roundware project, Access American Stories (http://www.si.edu/apps/accessamericanstories), used Roundware to gather bilingual crowd-sourced descriptions to increase accessibility for visitors with low vision to one-hundred objects in the American Stories exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The project added voting, liking, and flagging, and more flexibility was added to tagging comments.

Voices:FAMSF is further extending Roundware in ways that may become very significant to the museum community, particularly a new feature that provides the ability to tag visual images to audio comments. This object-specific wayfinding aid is an important step forward for outdoor locations where GPS may not pinpoint locations as specifically as is needed. Beyond wayfinding, the addition of image association to Roundware has many other interpretive and educational uses in museums. For Voices:FAMSF, we also developed a feature that allows users to choose to listen to museum voices, community voices, or both, and change that choice as often as desired.

Because FAMSF includes two museum sites, the de Young and the Legion of Honor, we developed a feature that allows themed “skins” to be overlaid on locations.

Another unique feature of Voices:FAMSF is access to in-depth interpretations of the art and architecture included in the app, through the online site (http://famsf.org/about/voices/).

This bridge between the on-site experience and a pre- or post-visit opportunity to learn more about artworks is an extension of Roundware’s capabilities that’is extremely relevant to educational and interpretive uses in museums. In essence, it marries an in-the-moment, participatory soundscape experience with the ability to access longer, more in-depth interviews with museum experts, as well as written and visual information, best accessed when not with the artworks themselves.

Museum projects using Roundware are most successful when the museum gets involved in wanting to create something new and different and evolving. Voices:FAMSF is an example of this desire in action. Through working on the app, Brad Erickson, senior developer at FAMSF, became very interested in continuing to build Roundware. His initial work was motivated by his desire to help FAMSF create a high-quality app that would serve visitors and further the Museums’ mission. Erickson was also very much in support of the Museums’ decision to use a Free and Open Software (FOSS) framework to build Voices:FAMSF, for several reasons. FOSS allowed the museum to build upon existing code and functionality, thus benefiting from previous development work by Burgund and by other institutions such as the Smithsonian. It also meant that FAMSF’s development of the Voices:FAMSF app would be shared, while positioning FAMSF as a leading innovator creating a fresh, new visitor experience. Erickson was also inspired by the vision of Roundware’s creator, Halsey Burgund, to create a framework that could be a vehicle for its creator’s own personal sound art while also benefiting the larger museum community. Erickson cites Burgund’s decision to use the copyleft (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyleft) GNU General Public License (GPL) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GNU_General_Public_License) for Roundware, which allows everyone to use code contributed by anyone else, but also requires that publication of all new code contributions. This both protects Burgund’s personal work—Burgund retains copyright on his original work—and also ensures that additions and extensions to the Roundware source code benefit all users, since any creations built using Roundware are GPL licensed. Other contributors retain copyright to their own work as well, but grant Burgund an irrevocable license to use it. Erickson’s own vision is to create a basic FOSS Roundware app that any museum could customize. He’d like to see Roundware with photo, video, and multilingual support in use in every museum or national park in the world.

The process of innovation is never hiccup-or risk free, and Voices:FAMSF has been no exception. Many frustrating issues with functionality became apparent early on in our app-building and beta-testing process. It may be difficult or problematic to demonstrate beta versions to stakeholders at various stages of app development; thus museums need to have buy-in and trust in the process from funders and other key stakeholders. The Voices:FAMSF team was able to demonstrate steady progress and agree on solutions and new feature development, but teamwork, collaboration, and the full support of stakeholders (from the director and board to the IT director to the Museums’ marketing team) were crucial to the project’s success at every stage.

In summary, Roundware isn’t just basic audio-tour software. At its core, Roundware creates a relationship between an artist, app developers, the museum, and its visitors, weaving them all together in a continuous field of co-creation and contribution. Roundware is enriched by the Museums’ specific needs for new features and functionality. The Museums’ educational and interpretive content is enriched by the inclusion of visitors’ voices and opinions, and the Museums’ relationship with its visitor community transforms from unidirectional to bidirectional. Instead of the museum simply delivering authoritative content to the visitor, visitors become stakeholders in the Museums’ collections and co-creators of interpretative content, thereby becoming more engaged and invested in looking at art.

3. Voices:FAMSF beta evaluation

by Alexa Beaman

Introduction

For this project, I conducted a formative evaluation of the beta version of Voices:FAMSF. The evaluation assessed visitor engagement, app concept, and app usability. These measurements directly tied to the Museums’ app goals and objectives. SurveyMonkey was utilized as the survey platform. The evaluations took place in the de Young sculpture garden during November and December 2014.

Participants completed the survey after downloading and using Voices:FAMSF on their personal mobile devices to assess the criteria above. Fifty participants were studied in order to ensure the data was statistically significant (Diamond et al., 2009). Participants consisted of museum members and non-members who were randomly invited from the Museums’ e-mail list. Those who received the invitation self-selected to participate, based only on the information that they would evaluate a “new interactive mobile app” and help the Museums refine their use of new technology. Participants agreed to test Voices:FAMSF with no advanced knowledge of app content-delivery methods or goals. The average age of participants was 50.8 years, which skews slightly younger than the average age of FAMSF visitors, which is 57.7 years. Fifty-two percent of participants reported that they often or sometimes use mobile guides in museums, as opposed to the less than 1 percent that use mobile guides at FAMSF. We can infer that those who self-select to test an interpretive guide are slightly younger and inherently more open to mobile guides than the general FAMSF museum-going audience. Below are highlights of the survey as they relate to this paper. The full Voices:FAMSF Beta Survey can be requested by emailing spressley [at] famsf.org.

Evaluating the app in beta was crucial to demonstrating how visitors responded to the app before it was launched in February 2015. The evaluation helped the Museums and Earprint Productions better gauge if and how improvements to the app could and should be made. The Voices:FAMSF team was acutely aware that the idea of visitor-generated and non-linear content presentation was a major shift in course for the Museums’ interpretation program. The team needed to determine if what they termed “app concept” was a direction that encouraged visitor engagement with the art and met with visitor satisfaction. The team was also aware that the beta version of Voices:FAMSF still had significant usability bugs. There was concern that these bugs might negate positive responses to the evaluation questions.

Visitor engagement

The Museums’ education department was very clear in articulating what they hoped to accomplish in terms of visitor engagement. They identified six indicators of how they hoped visitors would engage with art:

- Look more closely at works of art

- Spend more time looking at individual works of art

- Discover more about art

- Enjoy my visit more

- Feel inspired

- Discuss with others what I learned and saw

The first part of the survey asked participants to rate if their experience with the app had led them to either strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statements about visitor engagement.

As indicated in table 1, the results strongly indicate that per the Museums’ goals for the app, the majority of participants were engaged with art while using Voices:FAMSF.

App concept

The app presents content in a format unlike most museum mobile apps and audio guides. Thus, the Museums wanted to study whether visitors liked this approach and find out how visitors used the app. table 2 outlines participants’ responses to questions about the app concept. Participants were asked to rate if their experience with the app had led them to either strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree with the following statements: “My use of the app has led me to feel more likely to use an app similar to this one”; “My overall experience using the app was satisfactory”; “I would recommend this app to a friend”; “I would use this app if it were available in another part of the museum”; and “I prefer this app to a typical audio tour.”

The Voices:FAMSF team was pleased that the positive responses to the app’s concept were relatively high considering the low usability satisfaction responses discussed in a later section. These percentages of visitor satisfaction exceeded expectations.

Table 3 highlights different ways in which participants used the app.

Overall, these results indicate that the majority of participants understood how to and did listen to audio when using the app, and were able to make a choice to listen to either museum or community voices, or a mix of both. Although a lower percentage (33 percent) of participants used the “Speak” feature and recorded content when using the app, this is typical of crowd-sourced content (Proctor, 2012). The Museums’ goals are for meaningful content generated by “inquisitive and observant” visitors, rather than for a specific percentage of visitor/contributors of recorded content. Further inquiries into visitor satisfaction with museum versus community voices will help the Museums refine how to, and if they will, choose to curate community contributions.

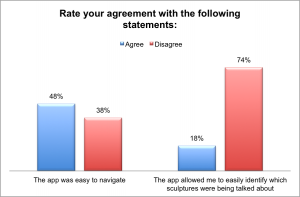

Usability

Both the Museums and Earprint Productions had anticipated usability issues around the imprecise nature of GPS. Indeed, in terms of measuring usability, participants’ largest issue was discerning which audio recordings corresponded to each specific artwork. Table 4 highlights participants’ responses to questions surrounding app usability.

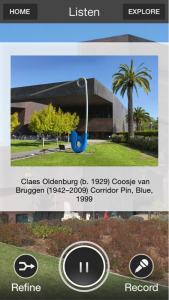

Not quite half of the participants agreed that the app was easy to navigate. This clearly indicates a need for improvement. Qualitative data highlighted participants’ inability to easily locate user information. A redesign of the information page and icon is currently underway. The most significant usability issue was, as expected, the imprecise nature of GPS and the user’s inability to easily identify which work of art was being discussed. Seventy-four percent of participants did not feel that the app allowed them to easily identify which sculpture was being discussed. The Museums and Earprint Productions are addressing these concerns by adding a feature that allows associating object images with individual comments. Figure 5 illustrates how, for example, Oldenburg’s Corridor Pin, Blue (1999) will appear when comments referring to that work are played. The Voices:FAMSF team’s hope is that app users will only glance briefly at their screens to confirm which artwork is being discussed and continue to pay close attention to the original work of art, but further testing will need to be conducted once this feature is released.

4. Conclusions

Overall, the Voices:FAMSF team felt that the survey provided evidence to encourage stakeholders to allocate additional resources toward audio interpretations of an experiential nature. The Museums are currently planning for new audio content for their permanent collections and will incorporate successful features of the Voices:FAMSF model. The usability concerns are valid and remind those of us in the non-profit world that when it comes to technology, we compete for user satisfaction with apps created by companies with behemoth resources. In general, app users care very little about the maker’s budget; they expect a smooth, fast, and flawless experience.

The Voices:FAMSF team felt strongly that the programming hours dedicated to crafting Roundware into a customizable museum interpretive tool be shared with the wider community and wanted all work to continue in an open-source platform. As Voices:FAMSF is further developed by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Earprint Productions, and hopefully other institutions, usability will improve and be shared. It is also hoped that other institutions might experiment with and share findings about the validity of a location-sensitive, customizable, non-linear soundscape that mixes community voices and museum voices as an interpretive tool. A summative evaluation of the app is planned after its launch. Voices:FAMSF team members all expressed a desire to refine certain aspects of the evaluation in its next iteration. The common sentiment expressed was that this formative evaluation helped them think about desired information in a more specific manner. This reminded the team of the importance of testing early and frequently.

References

Diamond, J., J. J. Luke, & D. H. Uttal. (2009). Practical Evaluation Guide: Tools for Museums and Other Informal Educational Settings. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Altamira Press.

Kerr, D. (2013). Smartphone ownership reaches critical mass in the U.S. Last updated June 5, 2013. Consulted January 25, 2015. Available http://www.cnet.com/news/smartphone-ownership-reaches-critical-mass-in-the-u-s

Novak-Leonard, J., J. Wong, & N. English. (2015). A Closer Look at Arts Engagement in California: Insights from the NEA’s Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, 15. Consulted January 25, 2015. Available http://culturalpolicy.uchicago.edu/sites/culturalpolicy.uchicago.edu/files/SPPA_CA_Report_Jan2015.pdf

Proctor, N. (2012). “Change and Innovation in the Museum Through Digital Participation.” In Nancy Proctor Keynote at Museum Next. Last updated Wednesday June 20, 2012, 2:47 p.m. Consulted January 1, 2015. Available http://vimeo.com/44404225

Cite as:

. "Voices:FAMSF: Testing a new model of interpretive technology at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco." MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015. Published February 1, 2015. Consulted .

https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/voicesfamsf-testing-a-new-model-of-interpretive-technology-at-the-fine-arts-museums-of-san-francisco/