Personal and social? Designing personalised experiences for groups in museums

Lesley Fosh, University of Nottingham, UK, Katharina Lorenz, The University of Nottingham, UK, Steve Benford, University of Nottingham, UK, Boriana Koleva, University of Nottingham, UK

Abstract

The designers of mobile museum guides are increasingly interested in facilitating rich interpretations of a collection’s exhibits that can be personalised to meet the needs of a diverse range of individual visitors. It is commonplace to visit these settings in small groups, with friends or family. This sociality of a visit can significantly affect how visitors experience museums and their objects, but current guides can inhibit group interaction, especially when the focus is on personalisation towards individuals. Our design approach embeds sociality from the beginning, treating personalisation as a social rather than computational issue, an idea that has potential reach beyond our own project. We describe our design of an interactive visiting experience that lets visitors create interpretations of exhibits for their friends and loved ones that they then experience together, letting them scaffold a visiting experience by setting up prompts, information, and emotive triggers around individual exhibits. The result is a personalised, one-off mobile tour crafted by the visitors themselves to directly communicate interpretations to others that they know well. We present the results of two pilot studies in which this approach was used in different museum settings and with different types of small groups. We report on how visitors designed highly personal experiences for one another, analysing how groups of visitors negotiated these experiences together in the museum visit, and revealing how this type of self-design framework for engaging audiences in a socially coherent way leads to rich, stimulating visits for the whole group and each individual member. We present a replicable design for engaging audiences, increasing visitor participation, and realising the potential for meaningful group experiences.Keywords: Groups, social, personalization, engagement, participation, gifting

1. Introduction

Museums and art galleries have a long-established relationship with mobile technology, from the early audio guides of the 1950s to the more recent downloadable applications that visitors run on their own devices. The common goal for those designing these technologies is to engage visitors with the artefacts on display, often by providing a wider range of information or interpretation than can be displayed on physical labels and exhibition guides. More recent advances in this field include context-aware guides (Wecker et al., 2011), augmented reality (Elinich, 2014), and tabletop displays (Horn et al., 2012), with the underlying technologies allowing visitors to access increasingly large stores of information.

Whereas museums traditionally provided a single interpretation, it is becoming more common for institutions to support visitors in engaging with multiple narratives and interpretations (Whitehead, 2012). Simon goes further to argue that visitors should be active participants rather than passive consumers of interpretation, defining participation as allowing visitors to use museum content as a basis for creating, sharing, and connecting with one another (Simon, 2010).

A hugely diverse range of people visit museums, and providing access to multiple interpretations of exhibits increases the chance of each visitor finding his or her own way to connect with them. Simply providing different types of interpretation for visitors to select from can threaten to overwhelm visitors with more information than they can make sense of. This has prompted an interest in personalisation: filtering or adapting content based on the individual visitor’s unique preferences, prior knowledge or visiting style (Ardissono et al., 2012).

Most people, however, visit these settings not alone, but with friends, family, or loved ones (Falk, 2009). The social context of a visit shapes how visitors experience collections, and further challenges can arise from visitors having to divide attention between museum artefacts and interpretation on the one hand and maintaining the social dynamic of their visit on the other (Tolmie et al., 2013). Current guides can inhibit group interaction, especially when the focus is on personalisation towards individuals. Previous attempts to personalise to groups of visitors rather than individuals have included the INTRIGUE tourist recommendation system, which combined preferences from multiple group members to recommend attractions for a group visiting a city (Ardissono et al., 2003). The recommendations were based on visitors’ general interests or practical requirements, but we feel that personalising to groups in museums and galleries is a more complex task that must involve not just broad recommendations but the delivery of tailored interpretations in a way that accommodates the social nature of group visiting.

Our research addresses the combined problem of delivering personalised interpretations in a way that supports group visiting. In this paper, we explore a new approach to the problem: that of “gifting” interpretations between visitors who know each other well. We draw upon two studies that tested the approach, before discussing the lessons we learned and how they might be used in future implementations.

2. Gifting as a socialised approach to personalisation

The motivation for our approach to personalisation comes from the practice of gift giving. People give gifts to each other for reasons of obligation and reciprocity, and the exchange of gifts is important in building relationships and solidarity (Mauss, 1990). Choosing or making a gift for someone involves drawing upon knowledge of interests, personality, and relationships, which imbues the gift with both emotional and instrumental meaning (Sherry, 1983). Gifting is typically embedded in a social occasion involving a gift giver, a gift recipient, and possibly onlookers, and the gift exchange involves the recipient carefully managing assessments to decode the gifter’s intent and provide an appropriate response (Robles, 2012).

The literature suggests that gifting is a powerful mechanism that involves deep personalisation and is typically embedded into a social occasion. Moreover, people may often visit places as part of a gift experience, such as a treat or holiday. We therefore hoped that by getting visitors to design experiences as gifts for each other, we could harness the mechanism to create deeply personal experiences that are also inherently social. We sought to realize this approach by inviting visitors to design interpretations of exhibits that were specifically tailored for others that they know well, that would be delivered as part of a mobile guide. This generates a personalised gift experience that is made by one person to communicate a personal interpretation to another that they know well. We hoped that by tapping into the interpersonal knowledge of visitors, we could facilitate the creation of experiences that are at once personal and social, engaging the visitors who had either designed for a friend and are eager to find out how it is received, or are on the receiving end of a highly personalised interpretation.

Instead of asking visitors to design an interpretation from scratch, we provided a template to use as a basis for their designs. Our template was based on our previously designed experience for pairs of visitors at a sculpture garden (Fosh et al., 2013). The experience consists of a tour of a set of sculptures with, for each sculpture, a curated music track, an instruction for how to engage with the sculpture, and a portion of text to read after engaging. The delivery of the different components of the experience was structured to support social interaction between pairs of visitors using mobile audio guides. This provided a template that required visitors to choose a set of objects to visit, and for each object, a piece of music, an instruction for how to engage, and a portion of text (Figure 1). It was then our job to take the visitors’ designs and produce a mobile guide that delivered the content.

Figure 1: the five stages of the experience at each exhibit, with the elements a visitor can personalise highlighted in bold

We now describe how we realised this approach over two pilot studies investigating how visitors approached designing interpretations for their friends and loved ones. We report on the types of experiences that visitors designed and how the resulting experiences were used as part of a group museum visit.

3. Gifting an experience to a partner

Our first pilot study took place at the modern-art gallery Nottingham Contemporary. We focussed on an exhibition of around two-hundred artefacts from a range of periods, from contemporary sculpture to pieces of machinery and archaeological artefacts. Each was accompanied in the gallery with a basic information panel detailing the title, artist, date, and materials.

We recruited eight pairs of participants to take part in the study, six of whom were romantic couples and two who were close friends. Of the sixteen participants, ten were aged from twenty to twenty-nine years old, four were aged from thirty to thirty-nine years old, and two were over fifty years old. One member of each pair was invited to attend a design workshop at the gallery where they were able to choose a set of exhibits for their partner to visit, and the set of resources as per the template. They were guided through the design process by a workshop organiser and were asked to record their designs and rationales on a set of paper worksheets. They were given access to the Internet to listen to potential music choices and look up information. At the end of the workshop, they arranged a date to return to the gallery with their partner, when they could both use a mobile guide produced from their designs, implemented using the AppFurnace prototyping tool (AppFurnace, 2015). When they returned to the gallery, each partner was given a smartphone and a set of headphones. They were briefly introduced to the technology and left to explore the gallery at their own pace, while we video recorded from a distance to capture their interactions. Once they signalled that they were finished with their visit, the pairs were invited to take part in an interview to gather feedback on the design and experience.

Designs

The eight participants who designed an experience were briefed on the overall structure and template, but otherwise were given minimal guidance in their designs. They first identified a type of experience they wanted their partner to have, before choosing exhibits and resources to fit this experience type. Three main types of experience were identified by participants: personal experiences that were built around personal messages; educational experiences that they could use to craft an interesting message; and emotional experiences, intended to invoke an emotion such as amusement or enjoyment. Most participants, in describing the type of experience they wanted to design, used a combination of these types, such as a “personal emotional journey” or “a fun experience that might teach him something new.”

Each participant chose a set of five objects for their partner to visit. Their reasons for choosing objects were often related to their overall aim. Some participants had a specific theme in mind for their partner’s experience. Participant A wanted to design an experience for her husband B that was based on the theme of “mapping, drawing diagrams or making the world comprehensible.” She chose objects that reflected this theme, including a reproduction of a historical map. She said, “I thought it was an object that would appeal to [B]. He’s quite conservative in his taste as far as art is concerned and so I was trying to choose a mixture of objects that were quite traditional or widely accepted as art objects.”

Participants then chose the resources to build an interpretation around the object: a piece of music, an instruction to engage, and a portion of text. Again, we provided guidance in helping participants progress from an abstract idea of their intended experience to a more concrete piece of music, instruction, or text by encouraging them to think about physical and thematic aspects of the objects, their partners’ tastes, and their own interpretations. Music and instructions were often used to reinforce themes, set a mood, or even trigger shared memories, as was the case with participant C’s experience for her boyfriend D, with a piece of art that resembled a large sound system: “I’ve said to go as close to it as possible and stare into the speaker, then I’ve picked a song that’s reminiscent of when we used to go out clubbing a lot, to try to get him to remember and feel good about the act of memory, through the song.” Finally, the text was used by participants to deliver information they had found about the object or explain their personal reasons for choosing it. Figure 2 shows C’s full design.

Visits

Seven of the eight participants brought their partner to the gallery for a visit in which they could both use the experience that had been designed; one pair was unable to visit within the study period. Here we describe a selection of behaviours that demonstrate how pairs of visitors negotiated the experiences together, to show how the resulting experience played out during the joint visit.

Six of the seven pairs chose to stay together for the experience, while one decided to split up, as was their usual visiting pattern. In the pairs that visited together, the person who designed the experience often took the lead, showing and demonstrating how he or she intended the experience to play out. Further, being together gave the designer the opportunity to add explanations and answer questions about their designs, and to engage with their partner’s own interpretations, which were not always in line with the design.

We found that the effort involved in designing an experience for another—in a similar way to choosing or making a gift for someone—created a two-way social obligation. The recipient of the gift always saw the experience through to the end and reciprocated by giving their time and complying with the experience. Meanwhile, the designer, interested in seeing the experience carried out successfully, ensured the recipient got the most out of it by themselves engaging with the experience, actively supporting their partner, and often leading the way.

Some designs entailed an element of social risk, especially those that were designed to deliver an intimately personal message or required the recipient to perform a physical action in the public setting of the gallery. This was evidenced by frequent nervous laughter and monitoring of the recipient by the designer, and occasionally even playfully apologising, as was the case when participants C and D negotiated the “low point” of their emotional journey (Figure 3), where a stone gargoyle was used to confront D with his fear of death and comfort him through C’s interpretation (Table 1). D’s response—smiling and reassuring C that he was OK—was typical of those receiving such provocative, deeply engaging interpretations.

The study showed that gifting interpretations between pairs was an effective way to build deeply personalised gallery experiences, drawing upon past experiences, shared memories, and personal details. The resulting experience, carried out alongside the person who crafted it, was intensely social, involving work from both parties to maintain the experience and support one another. It was not without its challenges, however. For some visitors, the intensity of gifting such a personal interpretation to a partner entailed an element of social risk, which had to be managed by laughter and reassurance. Our study looked at only couples and pairs of close friends, so our next step was to take the lessons learned and apply them to larger and more diverse visiting groups.

4. Gifting interpretations within groups of friends and family

Our next study took place at Nottingham Castle Museum, a traditional art and local history museum on the site of a medieval castle. We chose to focus on the exhibition named Every Object Tells a Story, a collection of decorative and historical artefacts. The exhibition covers two mid-sized rooms adjacent to each other. Artefacts in the collection were mostly encased in glass cabinets, with interpretation provided separately in a set of paper exhibition catalogues, ranging from simple captions including a title, information on materials, and date to sometimes even curators’ explanations of the objects and how they came to be in the collection.

We first needed to expand the previous model of one person designing an experience for another so that it could be applied to groups of three or more visitors. The gift-giving literature tells us that in traditional gifting scenarios, gift givers are highly concerned with mutuality and equipollence (Wooten, 2000), and that a lack of reciprocation between participants can result in anxiety (Robles, 2012). We also found in the previous study that designing an experience for another person could be more rewarding than receiving an experience. We therefore decided to build direct reciprocation into our model and allow each member of the group the opportunity to design an experience for others. This led to a model in which each group member could choose one object for each other member of their group and design the interpretation for the object with that person in mind. These were then collected together into a mobile tour for all members of the group to use. For example, in a group of four friends, each person would pick three objects: one for each of the other member of the group. The tour would then consist of twelve objects, with each member having chosen three objects and having three chosen for them.

The twelve visitor groups we recruited included six groups of adult friends and six families, including one or two parents and one or two children. Of the twenty participants that made up the adult groups, thirteen were twenty to twenty-nine years old, three were thirty to thirty-nine years old, and four were over fifty years old. In the family groups, all the parents were aged between thirty and forty-nine, and the children were aged between three and ten. The visitors attended workshops in their groups where they were able to choose their museum objects and design the interpretation to go alongside (music, instructions, and text). They were invited back to the museum to use their experience in their groups, before being interviewed.

Designs

The adult groups approached the design task in a broadly similar way to the individuals in our previous study, tailoring to the recipients’ interests and/or drawing upon their relationships to give a personal interpretation. However, as the overall experiences were contributed to by three or more people, they were not linked together with an explicit theme or experience type, as they had often been when only one person designed the experience. Interestingly, there were similarities in how members of the same group approached their designs and the types of objects they chose. For example, three students made up a group from China; they all chose objects of historical and cultural significance, chose traditional music that matched the culture of the object chosen, and provided a traditional, informative interpretation for the text.

The designs from groups of friends tended to be thoughtful, but without the sometimes provocative intensity seen in our previous study. It was often the case that participants chose objects they could relate to the person they were designing for, and this was alluded to in the design. For example, participant R chose a miniature chair for friend S, which was intended to be a funny reference to S’s own tall stature. It was also common for participants to deliver playful experiences that were intended to be fun or unusual to carry out, often delivered through the instruction (e.g., for the miniature chair above, the instruction is to “Attempt to sit on an invisible chair”). By creating an engaging experience that was fun to carry out, visitors were able to embed more informative content, especially in the text, which they used to partly explain their choices with reference to the relationships and characteristics drawn upon and to communicate the interesting stories they’d found when researching the objects.

Four of the six family groups decided to pair up so that children and adults could help each other with the design task. When parents were designing for their children, they tended to choose objects that represented the child’s interests; for example, an elephant-shaped chess piece seemed the perfect choice for a child who liked both elephants and chess. The music choices tended to pieces that the children knew and liked, such as a nursery rhyme or a well-known pop song that all the family enjoyed. The text interpretations were mostly used to explain things to the children, reflecting that the parents wanted the experience to be interesting and educational. Children were also guided by the recipient’s interests when they were in charge of designing an experience. One seven-year-old child chose a decorative vase for his mother and used the text to explain: “I like the shape of the outside of this vase. It’s different from the vases you have at home. I’d like to have it in the house but there’s no room because you’ve already got lots of vases.” Meanwhile, the same child chose a sculpture of a lion for his eight-year-old brother, this time choosing to set the object to “Eye of the Tiger” by Survivor and instructing to “get down on all fours and act like a lion.” Again he used the text to explain his choice: “I firstly chose this object because you like lions, but also so that I can see you go down on all fours and look silly. I thought it would be funny.” In groups with two parents present, the choices made for one another tended to be thoughtful and often romantic—for example, relating the objects to things they like doing when the children aren’t around: “Imagine the jug full of red wine on a table surrounded by good food, on a sunny terrace (but with you in the shade).”

Children’s ability to complete the designs on their own varied across the different family groups. Most of the time, children teamed up with a parent to successfully create the designs, which involved discussing ideas and putting the choices down on paper. When children worked alone, the workshop facilitator was required to take on this role, asking children questions about objects and their family members to direct them towards accomplishing a complete design. Children were also helped with writing down their ideas and choices on the design worksheets. Groups did not typically share their designs with one another (besides who they were teamed up with, in the case of families), preferring to keep their designs as a surprise for when they returned to use the experience. Some children, however, felt they could not keep the secret and told their parents and siblings what they had designed in advance of using the experience.

Visits

When they returned to use the experience, all group members were given a mobile guide with the same set of objects, regardless of who designed for whom. The interface to the guide suggested an order by presenting the set of objects in a list based on where members would encounter them in the museum. However, this order was not enforced, so groups could choose to visit objects in a different order and decide whether to follow the order together or choose a separate order individually.

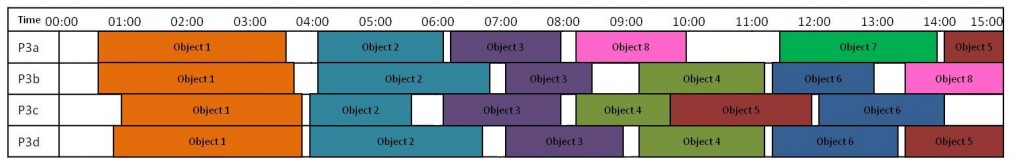

From analyzing our video recordings, we were able to roughly determine which objects group members were attending to during their visits. We were able to distinguish between groups who stayed together for most, or all, of the visit (two of the six friend groups and all but one of the family groups) and those that split up to visit objects individually or in subgroups. It therefore wasn’t always the case that the gifted interpretations were experienced with both the designer and recipient simultaneously present. While those who stayed together were able to discuss, comment on, and assess the objects in the moment, those who visited objects separately had to seek one another out to exchange feedback. Figures 4 and 5 depict the objects attended by members of two groups during their visits.

Figure 4: timeline showing the objects each member of Group 3 (four friends from an art class) attended to during their visit. They started their visit together but lost synchronisation as the visit went on.

Figure 5: timeline showing the objects each member of Group 2 (three friends from university) attended to during their visit. Two participants stayed together for the duration, while one began separately but rejoined the group towards the end.

The designer and recipient of each object experience was only revealed with the text interpretation that was displayed at the end of the experience—after the chance to listen to music, hear the instruction, and engage with the object. Visitors occasionally worked out whom the object was for partway through the experience—one commented sarcastically, “Oh I wonder who this is for”—and shared reactions to finding out the relationship at the end.

Unsurprisingly, the highest levels of social contact were between those visitors who stayed together during the visit and engaged with each other socially to navigate between objects, coordinate starting each experience, share reactions, and reflect on the interpretation. We were also able to observe social contact between those visitors who chose to visit objects separately. Sometimes this took the form of chance encounters, but there were occasions where visitors deliberately initiated contact by greeting one another, sharing reactions, and asking questions.

During the family groups’ visits, the children were often visibly excited, and some enjoyed themselves so much they insisted on repeating the experience. They were often less interested in reading the text portion of the experience as they were eager to visit the next object; therefore, the parents typically read the information for the children to listen to, only allowing the group to move on once they’d all had a chance to engage with the full experience and acknowledge who it had been designed by and for. Figure 6 shows a typical family visit.

Our overall impression from the video observations is that, given a semiflexible framework in the form of the mobile guide, visitors were able to organize a workable structure for their group visit and maintain a level of sociality in any case. As in the previous study, visitors were able to design interpretations that were specifically tailored to their group members and personalise these by drawing on the recipient’s interests and their interpersonal relationships. The personalisation was evident in the particular interpretations designed—such as the child drawing on his brother’s interest in lions—and the tone of the experience, which was suitable for the age of the recipient. All participants engaged with the entire experience, regardless of whether the particular object was personalised to them, and many commented that they had enjoyed the experiences that were for others as much as the ones that had been designed for them. Finally, the groups were able to use the flexibility of the experience to further tailor the visit to their group’s particular visiting style, by choosing whether to stay together or visit objects separately.

5. Lessons learned

Our two studies allowed us to explore in depth how groups of visitors approach designing a personalised interpretation for one another and negotiating a social experience in a museum or gallery visit. We now discuss what we have learned through studying the approach and how our findings might be applied to the design of personal and social-visiting experiences.

Personal

We found that by engaging with our approach, visitors were able to tailor experiences to one another’s individual characteristics. We have found additional evidence that the experiences were marked by a deep personalisation that made connections between museum content and visitors’ lives, feelings, and relationships. The approach generated a wide range of designs, including those that appear to be more about exploring personal relationships or, in some cases, just having fun, as well as those that had a more educational focus. Even when the focus of an experience was on having a good time, visitors were generally able to embed more didactic material within the engaging personal experiences, and were able to decide how to balance the two outcomes. This reflects an increasingly common trend for modern museums and galleries to place less emphasis on the “correct” interpretation of objects, instead wanting to support visitors in making their own interpretations (Whitehead, 2012). Previous studies have shown that these types of connections between museum content and visitors’ own lives can be integral to creating meaning (Ciolfi & McLoughlin, 2012).

Our studies were successful in provoking thoughtful and interesting designs from all the visitors who took part. Our workshops were set up to elicit visitors’ own ideas rather than influencing the design with our facilitator’s own suggestions. Using a predefined template for the experience—in our case, a piece of music, an instruction, and a piece of text—gave visitors a starting point for their designs and provided multiple opportunities to personalise to their chosen recipient. Our paper worksheets proved helpful in structuring visitors’ ideation processes, giving them a record of their aims for the type of experience and directing their thoughts towards the person they were designing for. That said, by doing the design work on paper, we were unable to allow visitors to try out their designs before putting them into the visiting experience.

Social

Sociality was embedded into the experience through the designs crafted by visitors to communicate interpretations to one another. We found that the effort involved in designing an experience for another provided motivation for the designers and recipients of experiences to support each other during the shared visit. The recipients saw the experience through to the end, complied with the experience, and offered assessment or thanks. Meanwhile, the designer had an interest in seeing the experience carried out successfully, ensuring the recipient was able to get the most out of it by themselves engaging with the experience, leading the way or monitoring from a distance.

We saw groups of visitors in our second study organise themselves in a number of ways when using the experience. The flexible structure of the experience allowed groups to visit in a way that suited their group visiting style and the different levels of social engagement with each another. By giving each group member access to all the designed experiences (rather than just their own) and only revealing who it was designed for towards the end, visitors were able to engage with the whole collection of experiences and use this as a basis for connecting with one another, regardless of whether they visited the objects together.

6. Conclusions and design implications

Our two studies suggest that our gifting method is a powerful approach for generating experiences that are both personalised and socially coherent. Sociality is first embedded in the content that visitors design for one another and is then negotiated in a shared group visit. That said, our findings suggest the success of our approach lies in its flexibility: first in designing an experience restricted only by the structure of the template and not in choice of content, and secondly in choosing and ordering how to use the experience as a group.

The mobile technology itself is very light, and there is no need for the technical complexity involved in designing, for example, augmented reality displays or installing indoor-positioning systems. The approach relies on visitors who are willing to design their own content, but once this has been done, they can find their own way around an exhibition and guide each other. What is needed, however, are public authoring tools and templates that make designing content easy to do, as well as suggestions and recommendations to guide them in place of our workshop facilitator. We anticipate there being some input required from curators in providing and packaging up the templates and resources that visitors can use when designing content, but that once this has been done, it will be the visitors themselves who draw upon these resources to weave their own personalised experiences.

References

AppFurnace. (2015). Consulted January 24, 2015. Available http://appfurnace.com

Ardissono, L., A. Goy, G. Petrone, M. Segnan, & P. Torasso. (2003). “INTRIGUE: Personalized recommendation of tourist attractions for desktop and handset devices.” Applied Artificial Intelligence 17(8-9), 687–714.

Ardissono, L., T. Kuflik, & D. Petrelli. (2012). “Personalization in cultural heritage: The road travelled and the one ahead.” User Modeling and User Adapted Interaction 22(1–2), 73–99.

Ciolfi, L., & M. McLoughlin. (2012). “Designing for meaningful visitor engagement at a living history museum.” Proceedings of the 7th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, New York, NY: ACM Press, 69–78.

Elinich, K. (2014). “Augmented Reality for Interpretive and Experiential Learning.” Museums and the Web 2014, N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds.). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published February 2, 2014. Consulted January 20, 2015. Available

http://mw2014.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/augmented-reality-for-interpretive-and-experiential-learning/

Falk, J. H. (2009). Identity and the museum visitor experience. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press Inc.

Fosh, L., S. Benford, S. Reeves, B. Koleva, & P. Brundell. (2013). “See Me, Feel Me, Touch Me, Hear Me: Trajectories and Interpretation in a Sculpture Garden.” CHI’13, ACM, 149–158.

Horn, M., Z. Atrash Leong, F. Block, J. Diamond, E. M. Evans, B. Phillips, & C. Shen. (2012). “Of BATs and APEs: An interactive tabletop game for natural history museums.” CHI’12, ACM, 2059–2068.

Mauss, M. (1990). The gift: the form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. London: Routledge Classics.

Robles, J. S. (2012). “Troubles with assessments in gifting occasions.” Discourse Studies 14(6), 753–777.

Sherry Jr., J. F. (1983). “Gift giving in anthropological perspective.” Journal of Consumer Research 10(2), 157–68.

Simon, N. (2010). The Participatory Museum. Museums 2.0.

Tolmie, P., S. Benford, C. Greenhalgh, T. Rodden, & S. Reeves. (2013). “Supporting Group Interactions in Museum Visiting.” CSCW’13, ACM, 1049–1059.

Wecker, Alan J., Tsvika Kuflik, & Oliviero Stock. (2011). “Group navigation with handheld mobile museum guides.” In J. Trant & D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2011: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2011. Consulted February 17, 2015. Available at http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2011/papers/group_navigation_with_handheld_mobile_museum_g.html

Whitehead, C. (2012). Interpreting art in museums and galleries. Routledge.

Wooten, D. B. (2000). “Qualitative Steps toward an Expanded Model of Anxiety in Gift‐Giving.” Journal of Consumer Research 27(1), 84–95.

Cite as:

. "Personal and social? Designing personalised experiences for groups in museums." MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015. Published January 30, 2015. Consulted .

https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/personal-and-social-designing-personalised-experiences-for-groups-in-museums/