An evaluation framework for success: Capture and measure your social-media strategy using the Balanced Scorecard

Elena Villaespesa, Tate, UK

Abstract

Despite the vast amount of data at their disposal, museums struggle to measure the impact and value of their social-media activities due to the lack of standard metrics, consistent tools, and clear guidelines from funders. This paper attempts to define a performance measurement framework that may help museums define the set of measures and tools required to carry out this evaluation task. The evaluation tool proposed is an adaptation of the Balanced Scorecard, a framework developed by Robert Kaplan and David Norton and presented in the Harvard Business Review in 1992. As the authors define it, the Balanced Scorecard "translates an organization’s mission and strategy into a comprehensive set of performance measures that provides the framework for a strategic measurement and management system." The framework was used at Tate in order to study its applicability. During this process, the Balanced Scorecard was demonstrated to be an efficient method for gathering strategic information and defining performance measures. The next step was to put the framework into action, assess its usefulness, and analyse the insights and challenges that stem from applying it. This fieldwork was a practice of trial and error to test various methods and tools for collecting, analysing, and visualising the data with the aim of measuring the interaction and conversation created on these social media platforms. Based on a series of case studies evaluating the social media activities at Tate, this research evaluated which are the best metrics to use in the framework and how the data can be presented and turned into visualisations and actionable pieces of information that inform the decision-making process. This paper also reflects on the implications for museums of establishing a performance measurement system in terms of processes, organisation structure, and resources.Keywords: evaluation, balanced scorecard, social media, metrics, visualisation, performance measurement frameworks

1. Introduction

Social media offers a great opportunity for museums to communicate, interact, and engage with their audience. For several years museums have been developing interactive digital projects in order to foster participation and get the audience involved creating, rating, or sharing content. As funded organisations, museums need to report to their public and private funders. In the last two decades, there has been a shift in what to measure within museum evaluation, moving the focus from accountability and outputs to evaluating outcomes, impact, and value. As Weil (2003) claimed, “The museum that does not prove an outcome to its community is as socially irresponsible as the business that fails to show a profit. It wastes society’s resources.” How museums can demonstrate the impact and value of their social-media activities is a hard question to answer, but it should go beyond just counting the number of followers, as this figure has a limited capability in measuring success within this environment. Sometimes, the evaluation challenge takes one step back in the process, as museums also struggle to define their objectives using social media sites (Malde et al., 2013).

This paper attempts to define a performance-measurement framework that will help museums establish a set of measures and tools required to put this impact- and value-evaluation task into practice. We propose using an adaptation of the Balanced Scorecard as a method to capture strategic objectives and establish a performance measurement system. This framework is applied to Tate in order to assess its validity and implementation challenges.

2. The Balanced Scorecard

The Balanced Scorecard is a performance measurement framework that “translates an organization’s mission and strategy into a comprehensive set of performance measures that provides the framework for a strategic measurement and management system” (Kaplan & Norton, 1992). As per this framework, the mission of the organisation is at the core of the evaluation process: “the start of any performance measurement system has to be a clear strategy statement. Otherwise, performance measures focus on local operational improvements rather than on whether the strategy is being achieved.” The Balanced Scorecard measures performance towards the organisation’s strategic mission and goals from both an internal and external point of view from four perspectives: financial; internal business processes; learning and growth; and the customer. Each perspective of the Balanced Scorecard includes objectives, measures, and targets to be met (Figure 1).

Although the Balanced Scorecard was originally developed for the business sector, different authors have attempted to apply it to the non-profit sector. Kaplan, one of the creators of the Balanced Scorecard, actually introduced two modifications so it could fit into the requirements of non-profit organisations. The first change was to put the mission at the top of the Balanced Scorecard, representing accountability between the organisation and society. The second change was in regard to who the customer is. While in the business sector the customer is the same person who pays and receives the product or service, in the non-profit sector there are funders or donors who pay and benefactors that receive the service. To reflect this situation, Kaplan proposes two perspectives positioned in the Balanced Scorecard at the same level (Figure 2).

The Balanced Scorecard has been adjusted by adding, removing, or renaming the perspectives originally proposed, and to date we can find a number of attempts to apply it to the museum sector (Fox, 2006; Falk & Sheppard, 2006; Boorsma & Chiaravalloti, 2010; Zorloni, 2012).

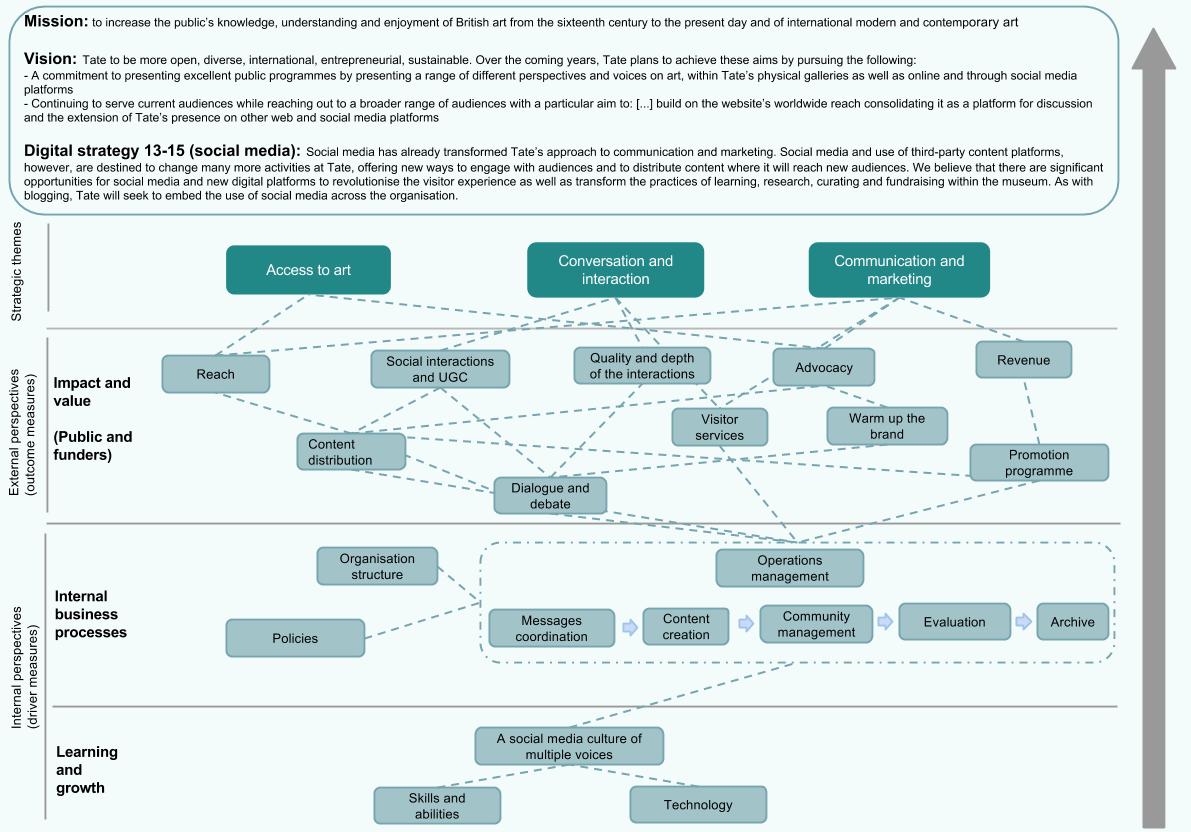

3. Defining a Balanced Scorecard for Tate’s social-media activities

The Balanced Scorecard can be applied from the macro point of view of an organisation or to a specific organisation’s activity (Figure 3). The second of these is presented in this paper, where a modified version of Kaplan’s non-profit Balanced Scorecard is applied to Tate’s social-media activities. Starting from the top, this section provides firstly a brief review of Tate’s mission and vision, and then proceeds to examine the strategy behind the social-media activity. This step will help to identify the strategic objectives and understand how Tate is operating in the social-media arena. In order to compile this information, the following tasks were carried out: analysis of strategic documents such as strategies and policies, mapping of the current activities, and semi-structured interviews with people across Tate who work on social-media platforms. These interviews allowed us to dive into the details of the different platforms and accounts and their individual objectives, as well as to understand the opportunities and challenges of this medium. The interviews included a number of questions aimed at addressing the four perspectives of the Balanced Scorecard.

4. Social media at Tate

Tate has a massive presence on social media, and the plan is that it will only continue to grow. Tate’s website (http://www.tate.org.uk) has evolved greatly in the past decade, from a very static site that featured visiting information and a calendar of events to a social website where users can participate in online conversations and debates, and on which there are also interactive areas like Tate Kids and Tate Collectives allowing users to upload their own content. Social features have also been added to the site, such as sharing buttons, Twitter real-time feed widgets, commenting, and a feature that allows users to create their own online albums with artworks and archive items, to which they can upload their own art and then have the possibility to tag and share them.

Not only has the website become more social, but Tate has also opened profiles on different social-media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and Pinterest that are updated on a regular basis. There has been a rapid increase in the number of accounts and number of people from different departments involved in these activities and a great diversification in the use of these social platforms. The spectrum of initiatives undertaken on social media is very wide, ranging from updates announcing the opening of an exhibition to an interpretation tool used in the galleries. New postings are regularly written in these platforms, including promotion of exhibitions and events, contests, links to content on the website such as blogs or videos, news announcements, or visiting information.

Strategic thinking behind social media at Tate

Tate’s mission and vision set the strategic intent of the galleries’ activity and define the core values and priorities that the strategies need to subscribe to. Tate’s mission is “to increase the public’s knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of British art from the sixteenth century to the present day and of international modern and contemporary art.” Social media, according to Marc Sands, former director of Media and Audiences, allows Tate to work in those areas:

You can take that as a brief and develop a strategy based on that simple statement. Tate’s mission is about knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of art, then I think that social media can meet all three elements and I don’t think it should be viewed as in competition with or as exclusive to, it’s just another means by which we can engage with audiences in the work that we do.

Tate’s vision for 2015 in regard to audiences states that:

… diversity of viewpoints is integral to the concept of the public realm. Today more than ever, the museum is a place where ideas, experiences and opinions are exchanged. There will always be a role for the expert, but the evolution of communication technologies offers unrivalled opportunities for people to contribute from their own personal perspective.

More specifically, it highlights that Tate will continue “to serve current audiences while reaching out to a broader range of audiences with a particular aim to: […] build on the website’s worldwide reach consolidating it as a platform for discussion and the extension of Tate’s presence on other web and social media platforms.”

A series of strategic documents have been written highlighting the aims and objectives of Tate’s digital activity. The latest digital strategy document for 2013 to 2015, “Digital as a dimension of everything” (Stack, 2013), envisions the idea of how social media needs to be part of the different functions of the gallery:

Social media has already transformed Tate’s approach to communication and marketing. Social media and use of third-party content platforms, however, are destined to change many more activities at Tate, offering new ways to engage with audiences and to distribute content where it will reach new audiences. We believe that there are significant opportunities for social media and new digital platforms to revolutionise the visitor experience as well as transform the practices of learning, research, curating and fundraising within the museum. As with blogging, Tate will seek to embed the use of social media across the organisation.

Along this digital strategy, Tate has published a Social Media Communications strategy 2011–12 (Ringham, 2011). This strategy lists twelve goals for social media from the communication perspective, focusing on content distribution, reach of the messages, and return in terms of footfall to the gallery and revenue.

The strategic documents recognise the potential of social media to impact the visitor experience and the different Tate functions. There are broad aims about engagement and reach, but no specific objectives defined for this area. John Stack, head of Digital, notes that objectives are not clearly defined at this stage, and that there are different views on how to use social media, more aligned with specific departmental objectives than with its overall use. This is clearly demonstrated in interviews with people in charge of managing the different social-media accounts. Although some common themes appeared during these interviews, there is a huge diversity in the actual use of social media. In conclusion, there is maturity in the support from the top level of the organization, which believes in the potential of social media to contribute to the mission, as highlighted in the vision and digital strategic documents; however, there are no overarching and integral strategic objectives that align the whole organisation. Moreover, specific target audiences are not explicitly mentioned in the strategy and, for most of the social-media accounts, the definitions are very vague and commonly regarded in the interviews as something to be improved and more strategic about. This lack of definition has a direct impact on the evaluation practices, as there is no shared vision about what and how to measure.

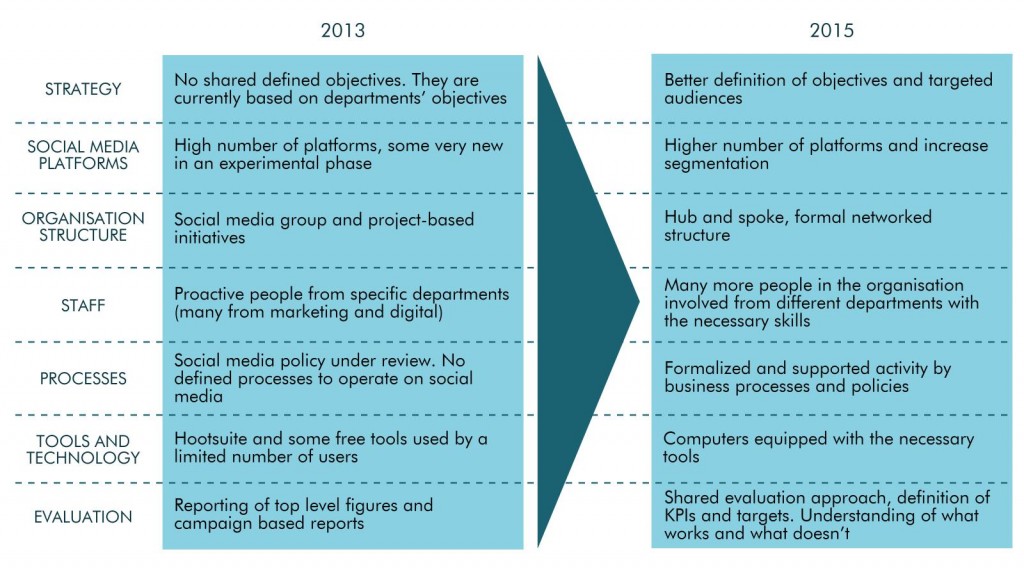

Figure 4, based on the analysis of the strategic documents and interviews, summarises the state of the current maturity of different organisational aspects in relation to social media and how they will be in the future. Tate needs to measure how this evolution is taking place and the external impact that these changes will have on the public.

Figure 4: state of the different organisational elements in 2013 and the plans of how they will be in 2015

5. Building the framework

In order to translate the strategy into specific objectives, a strategy map is used to identify the key factors to succeed in the strategy implementation process (Figure 5). Tate’s strategy map shows the activities and results that need to be measured, as well as the links between them and how they create value for the public. Following the diagram, each perspective and key success factor is explained, along with the measures selected, building at the end the Balanced Scorecard for Tate.

Internal perspectives

Internal initiatives are crucial to successfully achieving the strategic goals of the digital transformation project. The learning, growth and internal business perspectives are key to identifying and measuring the elements that drive value for the public now and in the future.

Learning and growth

Enabling staff and increasing their social-media knowledge and available working tools will be key success factors for growth and evolving towards a multiple-voice organisation. Three main objectives can be identified under this perspective:

- Create an organisation of many voices on social media

- Increase staff skills and abilities

- Provide tools and technology to work with social media

Internal business processes

From the internal business process perspective, a series of operational tasks involved in managing the activity on social media need to be supported by a set of processes and policies and an internal network structure. We can identify three objectives from this perspective:

- Implement policies that will include safeguarding, moderation, and layered editorial control guidelines

- Increase efficiency in the operations management in tasks such as content production, monitoring responses, and archiving the user-generated content

- Establish a governance and organisation structure that will increase communication and collaboration among departments

External perspectives

From the external perspectives, we will need to select measures to capture the impact on and value generated for the public and use this evaluation as evidence for funders. As previously mentioned in the paper, the objectives vary greatly for each of the accounts. One of our interview questions was what success looks like. There are clear differences in the definition of success given by people managing the different accounts, from the extreme poles of Tate’s shop’s Twitter account, where revenue is the best level of success, to social interactives in the gallery, where an in-depth comment in response to a debate would be the best possible achievement. In addition to the different specific objectives of each account is a series of interlinked strategic themes that appeared during the interviews, especially when people commented on the overall impact of social media and on what these platforms allowed them to do in terms of interacting with audiences.

Access to art

The first key theme that appears in both the strategic documents and interviews is how social media can provide access to the Tate collection and the content generated around it. This can take the form of videos, blogs, articles, or artwork images that are linked to or embedded in these platforms. The nature of social media and the potential reach that the content can have beyond the gallery walls provides an opportunity for Tate to reach out to a wider audience. One of the objectives is to distribute content to where users are; due to the possible viral effect of social media, the reach of this content can substantially increase. Providing access to art applies not only to where the user can consume the art content, but also to how the content can be presented in a more informal and friendly way through language, tone, and format.

Conversation and interaction

The second objective within this perspective is to engage with the users. Words such as participation, interaction, engagement, co-creation, conversation, dialogue, or user-generated content were repeatedly mentioned in the interviews. The strategy describes the audience as contributors and collaborators. A clearly defined strategic goal contained in both strategies states that these are platforms for multiple voices, discussion, and debate. Nevertheless, as shown in the objectives and definitions of success, the meaning of engagement at Tate varies for each different department and, as a consequence, creates an internal conflict.

The concept of engagement was mentioned in the interviews, for instance when talking about aspects such as visitor-generated interpretation through the gallery interactives, which allows people to offer their perspective of an artwork; members commenting on the Facebook page on how they revisited an exhibition multiple times using their membership; an image that gets many likes; or the texts people write before a reblog on Tumblr. A range of social actions can be considered engagement, but the depth of this interaction and the ‘effort’ from the user can go from a simple click to like a post, to writing a long and elaborate comment responding to a debate question on the blog.

Marketing and communication

One of the main uses of some of the social-media channels like Facebook, Twitter, and Google+ is to promote the exhibitions and events programme. A high number of the profiles are managed and regularly updated by members of the marketing team. The social-media communications strategy lists these specific communication objectives, which include: bring direct traffic to the website, distribute content, increase awareness of key messages, integrate social-media channels into the marketing campaigns, generate advocates and partnerships to increase online following, and generate revenue and footfall to the gallery (Ringham, 2011). The marketing and communication campaigns profit from the potentially viral distribution of content on these platforms, which is reflected in the increasing amount of content produced for this purpose.

6. A Balanced Scorecard for Tate’s social-media activities

Figure 6 shows the Balanced Scorecard for Tate, with potential measures for each of the objectives identified and the methods for data collection and analysis. For the internal perspectives, the measures selected aim to evaluate organisational change and the status of implementing a social-media culture. These are drivers or leading measures, and the methods to collect this data could include a survey of all staff to see the percentage of people who know about the strategy and are involved in social-media activities, and also a series of interviews or focus groups to get more qualitative information about strategic alignment, challenges, impact, and changes on working practices. The measures used in the external perspective will assess the impact on users and will require a mixed approach combining quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative data includes metrics such as number of likes, followers, comments, impressions, and traffic to the website. Qualitative data focuses on analysis of the content, sentiment, and quality of the user-generated content on these social-media sites.

7. Putting the Balanced Scorecard into action: Measuring conversation and interaction

The Balanced Scorecard proved to be a useful method for gathering strategic information and building a framework with the aim of evaluating the success of social media. The next step is to put the framework into action, assess its usefulness, and analyse the insights and challenges that stem from applying it. This part of the research has been a practice of trial and error to test various methods and tools aiming to analyse and visualise the data from different digital activities. The test presented in this paper focuses only on one section of the Balanced Scorecard, mainly in developing the metrics and working with different methods to collect, analyse, and visualise data to measure the interactions and conversations created while using these platforms.

Ongoing activity

Tate runs its social-media activity in several accounts, mainly Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram, and Google+. During the interviews, staff members were asked about their reporting needs, and their answers demonstrated differences in the degree of detail and the kind of information needed in their decision-making process. While senior management emphasised aspects such as the overall impact that social media has in creating great participatory experiences or contribution to total revenue, those who manage the accounts on a daily basis focused more on the detail and individual performance of each tweet, pin, or post. Consequently, different levels of reporting and different types of reports and dashboards should be used to present the information.

Based on these requirements, dashboards for different levels of reporting were developed:

- First, a strategic dashboard that captures the main key performance indicators of social-media activities to help monitor trends and get an overview of the activity.

- Second, a more tactical and operational dashboard linked to specific departments or account objectives and aimed at optimising the activity by performing an in-depth evaluation of which approaches work. To illustrate this example, a dashboard for a specific Twitter account was developed.

- Third and finally, a study of a particular Twitter activity (Tate Tours) is also presented.

Social-media dashboard

A social-media dashboard was created from a strategic point of view covering the main Tate social-media accounts. The dashboard features a series of metrics regarding community size, reach, and interactions, as well as some more transactional and conversational metrics such as traffic to the website, revenue, and percentage of visitors who have heard about the gallery from Tate’s social-media activities. Figure 7 shows an example of the type of visualisation museums could use for their reporting activity.

Figure 7: social-media metrics dashboard

At the top of the dashboard is a summary with the main highlights of the activity that took place that particular month. This is a key part of the dashboard, as it includes explanations of the changes, peaks, and other useful information extracted to interpret the data. The metrics included in the dashboard, such as reach and interaction rate, were positively regarded by the team as a tool for monitoring trends, and its implementation raised questions about the current activity.

The main issue stemming from representing all the accounts together is that each has different objectives required to be measured in different ways. Nevertheless, many of the accounts aim to interact with their users, even if the goal comes from marketing or learning. What this type of reporting fails to provide is an in-depth analysis of data and quality of the interactions; it is also missing a more detailed breakdown of what does and does not work. This takes us to the next level of reporting.

Twitter dashboard

To test the usability and efficacy of a more tactical and operational dashboard, a Twitter dashboard was created (Villaespesa, 2014). Museums have more than one profile for each social-media platform; for instance, they have accounts for their shop, members, specific audiences or art forms. This dashboard is an example of the type of reporting that could be used by museums to evaluate the success of the monthly activities of a specific Twitter account. It includes the following metrics: Tweets; replies to users; followers; impressions (as total volume, per tweet, and as a percentage of the total followers); interactions (total volume, per tweet, and as a percentage of the total impressions); distribution of the interactions; replies; retweets; favourites; and top 10 posts based on the interaction rate (Figure 8). At the top of the report, a summary with the highlights of the activity is included.

Figure 8: Twitter metrics dashboard

These two dashboards are examples of how a museum or gallery could gather and present social-media results on a regular basis, bringing the advantages of having a consistent and transparent reporting system but also posing some challenges, particularly when it comes to data-collection automation and interpretation. While the dashboards offer a visual presentation of key metrics and help to monitor trends and understand what works best, they have some limitations in showing the total impact. However, an explanation and breakdown of the results obtained for particular activities can also be included, which bring us to the next case study.

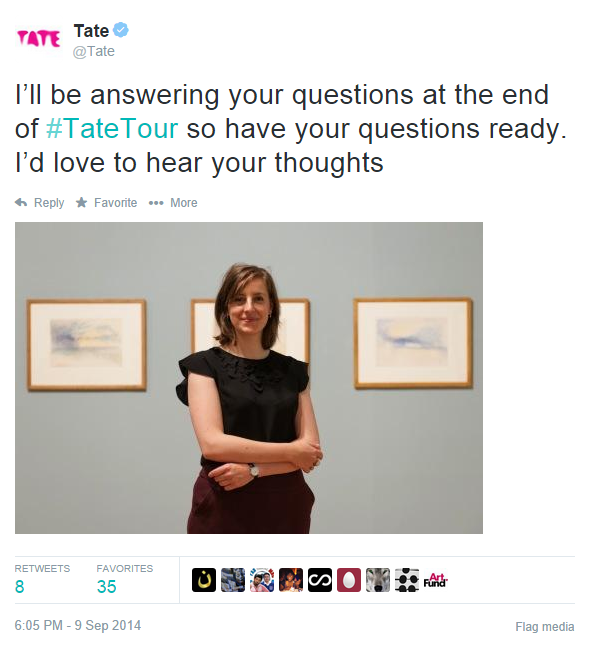

Twitter exhibition tours

Tate runs tours on Twitter where the curator of a particular exhibition takes social-media followers through the galleries by posting photos and videos and telling some interesting facts about artists or artworks in 140 characters. They are scheduled at a precise day and time to join the Twitter tour. Users need to follow the hashtag #TateTour to read the tweets, and they can include it in their tweets to send their comments or ask questions during the Q&A. These tours were carried out for several exhibitions. The case study presented in this paper examines the tour for the The EY exhibition: Late Turner – Painting Set Free (Storify, n.d.), held on Tuesday, September 9, 2014, from 6:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. BST and led by Amy Concannon, curator of the exhibition (Figures 9 and 10).

The key statistics of the activity gathered from Twitter Analytics are:

- Number of tweets sent by Tate: 28

- Impressions: 836,339 (average of 29,869 impressions per tweet)

- Retweets: 790 (average of 28 retweets per tweet)

- Favourites: 1,123 (average of 40 favourites per tweet)

- Replies: 79 (average of 3 replies per tweet)

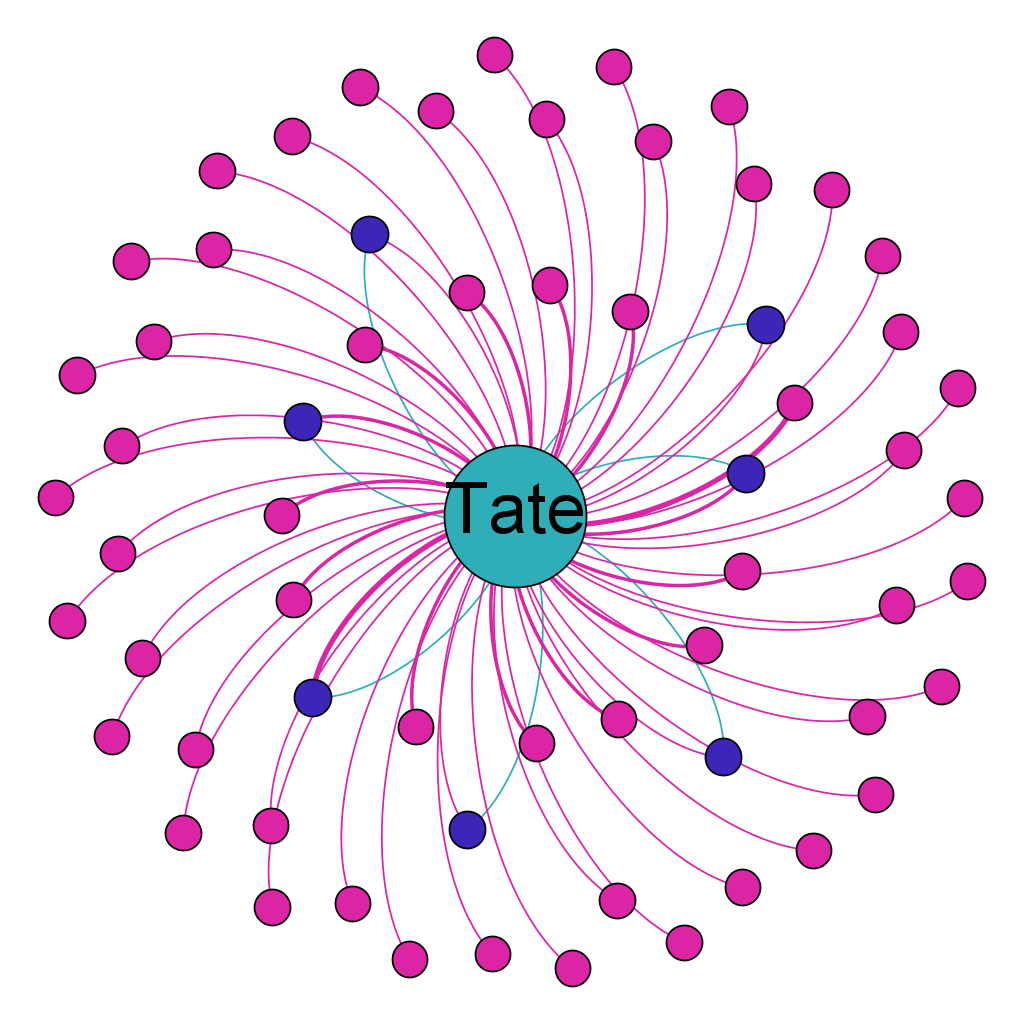

- Other interactions (clicks on images, videos, hashtag, user profile, links): 9,659

One objective of the tour is to connect with audiences and generate a conversation, especially at the end of the tour with a Q&A. In order to visualise the conversation between Tate and the followers, the social-network analysis tool Gephi was used to create the conversation graph (Figure 11). The analysis focuses on the conversations generated during the tour; therefore, the graphs only include replies to Tate’s tweets, those tweets asking questions using the hashtag, and Tate’s responses. Each of the nodes represents a user, and the edges are the tweets sent between the users. The colour of the edges represents the direction of the tweet. The edges in pink represent replies to Tate, and the ones in turquoise are sent by Tate in reply to users. The width of edges represents the volume of replies from a user to Tate during the tour. While most of the users only replied once, a few of them sent more than one tweet. The nodes of those users who sent a question and received a reply from Tate have been coloured in dark blue. The conversation graph has a clear ‘star’ shape which is common for popular tweets where there is a central user who generates the activity and users who reply to this (Cogan et al., 2012). The majority of the tweets were replies to Tate, and only a few exchange of tweets happened between users.

Figure 11: visualisation of the tweets from the #TateTour of the exhibition The EY exhibition: Late Turner – Painting Set Free

A total of 86 tweets from 63 users are represented in this graph. This included 7 replies from Tate to users and 79 replies from the users who followed the tour. Not all the replies included a question, so a response was not always required. The conversation analysis shows that there were a variety of replies:

- Users showing their excitement about the exhibition and their planned visit to Tate.

Got a ticket for Saturday!!!

Gorgeous, will have to get into town at some point to have a good look at these 🙂 - Users showing their enthusiasm for the artist and appreciation for the artworks being photographed or filmed and posted on Twitter.

The use of colour is just spectacular.

I have never seen this one before…magical!

I never knew a friend’s burial was the theme of this work. Thank you for the #TateTour of this #Turner show — what a wonderful idea! - Users thanking the curator for the tour. The tours provide access to the exhibition especially for those who do not live near the gallery and will not visit it.

Many thanks for #TateTour! We really enjoy following you!

My commute home was made so much more enjoyable by joining the fascinating #TateTour on Turner tonight! Thank you @Tate - Users sharing a personal memory or an emotion evoked by the tour or a previous experience seeing the artworks presented.

@Tate for many years I have enjoyed viewing his sketchbooks at the Tate the give a real insight into his finished work.

His later work for me makes me feel like a spirit or ghost painted the work. The color is like mist at dawn.

8. Conclusion

The research carried out at Tate shows how the Balanced Scorecard can be applied to a specific context: museums on social media. This research illustrates the value of applying business theories to museum studies with the proposal of a new framework and a tool for the sector. The methodology for implementing a Balanced Scorecard helps not only as an evaluation framework, but also as a performance-management system where objectives are clarified and common strategic themes identified. In this particular case, different points of views coexist within the main themes and must be approached with more tactical and operational reporting and analysis.

The Balanced Scorecard is just the framework, the structure of the final evaluation tool that needs to be filled in with the different metrics depending on the activity objectives and who is the final reader of the results. The data in the case studies presented in this paper was visualised in different ways, including charts, social-network graphs, and funnel reports, and using icons and drawings to illustrate the results of some key objectives. The flexibility that allows the framework to be adjusted for different fields is one of the reasons for the success of the Balanced Scorecard; however, it does not provide an accurate and guided definition of the metrics and methods that will finally be included. These need to be influenced by the practice of museum evaluation and also should take advantage of new methods that arise from the online environment. Further work experimenting with other case studies to evaluate social media can continue investigating the best way to analyse and present the data.

This research has focused on the implementation of one section of the framework, so further work needs to be done for its full implementation within the organisation. There are clear benefits of implementing a performance-measurement system, but there are also implications in terms of investment of resources and changes to processes in order to align the organisation with the use of the Balanced Scorecard and, as a result, introduce a data-driven approach to influence the decision-making process.

Acknowledgements

The research presented in this paper is part of the fieldwork I have carried out at Tate for my Ph.D. at the Museum Studies School, University of Leicester. I am very thankful to the members of staff at Tate I have interviewed and especially John Stack, head of Digital, for his support and valuable feedback. Special thanks to my supervisor Dr. Ross Parry for his continuous support, guidance, and motivation during this Ph.D. journey.

References

Interviews with the following staff members at Tate: Marc Sands, director, Audiences and Media; John Stack, head of Digital; Jesse Ringham, Digital Communications manager; Susan Holtham, Blog editor; Minnie Scott, curator, Interpretation; Carly Townsend, Marketing manager; Emma Evans, Marketing manager; Jen Ohlson, Tate Collectives producer; Kathryn Box, Tate Kids producer; Elizabeth Cooper, Marketing and Communications manager; Alex Carey, Digital editor, Research; Belinda Johnson, Publishing manager; Nick Aldridge, assistant producer; Helen Little, assistant curator; and Lucy Noakes, Online Shop administrator.

Boorsma, M., & F. Chiaravalloti. (2010). “Arts Marketing Performance: An Artistic-Mission-Led Approach to Evaluation.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 40(4), 297–317.

Cogan, P., A. Matthew, B. Milan, W. S. Kennedy, A. Sala, & G. Tucci. (2012). “Reconstruction and Analysis of Twitter Conversation Graphs.” Proceedings of the First ACM International Workshop on Hot Topics on Interdisciplinary Social Networks Research, 25–31.

Falk J. H., & B. Sheppard. (2006). Thriving in the Knowledge Age: New Business Models for Museums and Other Cultural Institutions, Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.

Fox, H. (2006). Beyond the Bottom Line: Evaluating Art Museums with the Balanced Scorecard, Los Angeles: Getty Leadership Institute. Consulted January 31, 2015. Available http://cgu.edu/pdffiles/gli/fox.pdf

Kaplan, R. S., & D. P. Norton. (1992). “The Balanced Scorecard – Measures that Drive Performance.” Harvard Business Review, 71–79.

Kaplan, R. S., & D. P. Norton. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action, Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

Kaplan, R. S., & D. P. Norton. (2004). Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kaplan, R.S. (2001). “Strategic Performance Measurement and Management in Nonprofit Organizations.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 11, 353–370.

Malde, S., J. Finnis, A. Kennedy, M. Ridge, E. Villaespesa, & S. Chan. (2013). “Let’s get real: A journey towards understanding and measuring digital engagement.” WeAreCulture24. Brighton: Culture24. Consulted September 30, 2014. Available http://weareculture24.org.uk/projects/action-research/

Ringham, J. (2011). “Tate Social Media Communication Strategy 2011–12.” Tate Papers 15. Consulted January 16, 2015. Available http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/tate-social-media-communication-strategy-2011-12

Stack, J. (2013). “Tate Digital Strategy 2013–15: Digital as a Dimension of Everything.” Tate Papers 19. Consulted January 16, 2015. Available http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/tate-digital-strategy-2013-15-digital-dimension-everything

Storify. (n.d.). Website with the tweets of The EY exhibition: Late Turner – Painting Set Free. Consulted January 31, 2015. Available https://storify.com/tate/tatetour-of-ey-exhibition-late-turner

Villaespesa, E. (2014). Looking at trends: a dashboard for Twitter Analytics, Consulted January 16, 2015. Available http://artsmetrics.com/en/dashboard-for-twitter-analytics/

Weil, S. (2003). “Beyond big & awesome: outcome-based evaluation.” Museum News, Washington, D.C.: American Association of Museums.

Zorloni, A. (2012). “Designing a Strategic Framework to Assess Museum Activities.” International Journal of Arts Management 14(2), 31–47.

Cite as:

. "An evaluation framework for success: Capture and measure your social-media strategy using the Balanced Scorecard." MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015. Published February 8, 2015. Consulted .

https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/an-evaluation-framework-for-success-capture-and-measure-your-social-media-strategy-using-the-balanced-scorecard/