#Taull1123: Immersive experience in a World Heritage Site (or augmented reality without devices)

Albert Sierra, Agència Catalana del Patrimoni Cultural, Spain, Eduard Riu-Barrera, Catalan Government. Heritage Department, Spain, Tarrida Sugranyes, Departament de Cultura de la Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Joan Pluma, Departament Cultura, Spain

Abstract

#Taull1123 is an immersive on-site experience that brings visitors of the Romanesque church of Sant Climent de Taüll (in the World Heritage Site Vall de Boí) to the past—precisely to the year 1123, when the apse of the church was painted with the iconic figures of God and saints. Those paintings were moved to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in Barcelona in 1920. Now, with this project, they are virtually returned to the walls of the church thanks to a mapping structure of six high-quality projectors. Over the real remains of the Romanesque paintings, the paintings of the museum are projected, exactly in their original places, which becomes a truly augmented reality experience, but without mobile devices, for all visitors. Every half hour, a nine-minute audiovisual show dives into the past and represents the moment of the painting, eight hundred years ago, with the different stages and figures, and finishes with a simulation of the paintings complete as they were. For the creation of this show, all fragments of the original paintings, now in the Museum, were photographed, studied, and digitally restored. The missing parts were reconstructed by analyzing the remaining parts and the architectural and pictorial patterns of the ensemble. The process of the different layers of lines and colors of the original painting was rebuilt, too, for recreating the painting by brush effects. The music was composed and arranged using real sounds of the surroundings of the church and medieval instruments, digitally remastered.Keywords:

1. Sant Climent de Taüll

The church of Sant Climent de Taüll in Catalonia, Spain, is the most famous of the nine Romanesque churches in the Vall de Boí. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 2000.

Figure 1: Sant Climent de Taüll. Photo: DGABMP (Dir. Gen. Arxius, Biblioteques, Museus i Patrimoni)/B. Masters.

The church is highly regarded on account of its architecture, but it is held in even greater esteem because, originally, its apse contained the most outstanding Catalan Romanesque fresco, a representation of God surrounded by tetramorphs and angels, the Christ in Majesty of Sant Climent de Taüll. By the beginning of the twentieth century, such frescos had begun to attract the attention of international art dealers. To prevent their export, there was a campaign between 1919 and 1923 to remove the Pyrenean frescos (Guardia, Camps, & Lorés, 1993), among them those of the church of Sant Climent, and they were housed in what is now the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC), where they have been on display ever since. (http://www.museunacional.cat/en/colleccio/apse-sant-climent-de-taull/mestre-de-taull/015966-000)

In 1959, a replica of the frescos was made for the church and until 2012, to a certain extent, restored the character of the apse. However, by 2012 the replica had suffered considerable damage: there were cracks in it, the colours had decayed and no longer reflected those of the original fresco, and it was mounted on metal supports that had originally been intended as temporary. The entire east end of the church suffered from damp, the roof leaked, and the central part of the apse floor could not be used. Furthermore, the number of people visiting the church had declined over the previous years, and it was necessary to improve matters to both attract more visitors and make it viable.

2. The project

It was with this in mind that a refurbishment project was planned, the main aim of which would be to restore the church’s splendour and enhance the quality of visits. The refurbishment, while including general improvements, would highlight the value of the church’s main architectural and pictorial features.

The project formed part of the “Open Romanesque” programme promoted by the Catalan Government Ministry of Culture and “la Caixa” Foundation (http://www.romanicobert.cat).

Despite the removal of the paintings, the walls of the church displayed numerous fragments of Romanesque frescos that were still in good condition, many of them of considerable size. The most outstanding was the framed figure of a dog on the north frontispiece, the representations of Saint Clement and Saint Peter on the columns, and those of Cain and Abel on the right wall of the presbytery.

The first option studied was that of installing a new replica in the apse. On previous occasions, such as at Sant Joan de Boí, this had been done by art restorers tracing the originals and painting the copy of the originals on the walls of the church (Riu-Barrera, 2000), while in the collegiate church of Santa Maria de Mur, a photographic reproduction technique had been used on a new photographic support called “PapelGel” (http://youtu.be/RBBcgiALoWU).

However, a study of the written and graphic documentation about the church of Sant Climent, especially that concerning the process for removing the frescos in 1920, led to a great surprise.

Figure 4: deep layers of paintings after fresco removal. Photo: Biblioteca de Catalunya, Salvany Archive.

In one photograph, it can clearly be seen how, once the frescos had been removed, shapes and volumes were still formed by deep layers of remaining paint that were hidden from view once the 1959 replica had been installed. Endoscopy confirmed the existence of these remains under various layers of whitewash and indigo-white. Once this was discovered, the recovery of these deep layers of original paintings in the apse became one of the project’s aims.

The alternative method considered then consisted of creating a virtual copy of the frescos to be projected onto the walls of the presbytery using spatial augmented reality techniques—projection mapping—since this would be compatible with preserving the deep layers of Romanesque paintings. This solution had a great advantage in that it enabled the recovery of the church’s authenticity to be combined harmoniously with the possibility of seeing the frescos in situ. In other words, it made it possible to display all of the church’s features, and this was of crucial importance for improving the quality of visits. There was an added advantage in creating an audiovisual presentation that would bring the importance and meaning of these frescos to life for visitors in a direct and moving way. Recent experiences with projection mapping in public spaces, like the work of Macula in Prague (http://vimeo.com/15749093) or Skertzò in France (http://www.skertzo.fr/), showed that this was a technically viable method.

The initial criteria for the project were demanding. The visual and architectural character of the church had to be preserved. This meant that any possible projection-mapping equipment would have to be concealed from visitors. Given the artistic quality and dimensions of the frescos to be projected, there would have to be maximum image quality for detail and colour. Furthermore, the projected images would have to coincide exactly with a three-dimensional surface containing the remains of the original painting. Moreover, this virtual replica had to be seamlessly incorporated into the general restoration of the church so that it would not be interpreted as an independent display, but rather be a complementary element to facilitate the artistic and architectural reading of the site.

A restoration project consisting of four components was eventually devised: a scientific study, architectural restoration, artistic restoration, and finally the projection mapping of the virtual replica.

3. The works

The work commenced with a study of all the written and graphic documentation available to historians about the frescos since they had been discovered in 1904, as well as about the church and the photographic documentation of the removal of the frescos and their subsequent installation in the museum in Barcelona.

At the church itself, a study of the walls showed that there had been two phases of pictorial decoration prior to the frescos we now know. The first of these was a white decorative band between the stonework, and then a secondary decoration of geometrical shapes, or of shapes inspired by vegetation, around the three lower windows, belonging to an unfinished first phase of the church. The painting around one of these three windows had been removed many years before, together with the rest of the Romanesque fresco, and taken to the museum in Barcelona. Archaeological excavation, meanwhile, made it possible to identify and recover the original paving in the centre of the apse, and the position of the original altar was discovered.

The frescos kept at the MNAC and the paintwork remaining on the church walls were also studied in detail during the process of artistic restoration to help with the recreation of the missing parts of the frescos, so that these too might be included among the images to be projected.

As we have noted, the project was conceived as integrated and unitary. Conservation techniques, illumination, contemporary architectural design, museography, artistic restoration, and the installations necessary for projection mapping were all interrelated facets of the same project, and they were implemented in a coordinated way.

The first restoration measures commenced towards the end of 2012 and consisted of draining the church perimeter to prevent damp. The roof too was repaired to prevent leaking. An intervention that had spectacular results was the removal of a modern beam from the framework of the roof that had been hiding one of the best fragments of the original Romanesque frescos on the frontispiece over the central apse, a helmeted figure playing a horn. An identical, symmetrical figure can be seen in the MNAC.

To make the apse accessible again, and to recover its cultural and liturgical uses, new wooden flooring was designed. It was conceived as being a light and reversible intervention which, separated from the walls, would make it possible to see the Romanesque original through its sides. A new altar was installed in the middle to replace the original stone one, and to the rear the flooring was lifted to form a pew in the presbytery, in which the projectors for the apse were to be concealed from view.

Figure 5: interior of the church of Sant Climent upon completion of the refurbishment with the new wooden flooring. Photo: SPA.DGABMP.

Installations at the church were also renovated. A notable aspect of the new interior lighting was the careful work carried out to display the fragments of the original frescos without them losing their place as part of the whole.

The church of Sant Climent possesses artworks of great interest, including three Romanesque sculptures and a number of Renaissance and Baroque retables. Their location was changed to improve their visibility and the circulation of visitors along the side aisles. The two museum installations to the sides of the door at the west wall were also renovated. One of them continues to exhibit a model of the church’s exterior, showing its original appearance (white with dark crimson decoration, as can still be seen on fragments of the bell tower). The other was supplemented with the addition of a new audiovisual presentation about the church’s history, which laid a special emphasis on the efforts of the architects Lluís Domènech i Montaner (Granell & Ramon, 2006) and Josep Puig i Cadafalch (Balcells, 2003) to both study and raise awareness about this church.

Work on the artistic restoration of the original frescos in the apse commenced with the removal of the 1959 replica, which was completely dismantled. Behind it appeared a layer of indigo-white, which almost completely covered the deep layers of paint. This meant that the manual restoration would be extraordinarily complicated. It meant removing this modern layer with the tip of a scalpel, inch by inch, without damaging the fragile remains behind. Exhaustive graphic documentation of the paintings in the apse and at the MNAC enabled reticulated plans to be made of the entire surface to be treated. The restorers were then able to use these to precisely identify the location of colours and figures hidden behind the modern layer of paint.

After four months of work to consolidate the deep layers and remove the modern layers of paint, the original layers of Romanesque painting were once again visible, and the gaps and cracks had been repaired as delicately as possible. The visual aspect of the whole had been much improved.

4. The virtual replica

The virtual-replica technique means that the church can be shown with the deep layers of Romanesque paintings, with the MNAC paintings in view, and with a hypothetical reconstruction of what the church would have looked like in 1123. To combine these three different stages, and after a study of the way people visit the church, it was decided to time the three different ways of showing the church in cycles of thirty minutes: three for the deep layers, seventeen for the MNAC paintings, and ten for #taull1123.

Figure 8: the three different aspects: the restored frescos, the preserved paintings including those from MNAC projected, and #taull1123. Photo: Eloi Maduell.

The development of the virtual replica commenced in parallel with the restoration work at the church. A three-million-point 3D laser scan was made of the entire area in the presbytery (one point every 3 millimetres). The resulting cloud of points was then simplified and meshed to be used as a surface on which the photographs of the frescos kept at the museum would be superimposed, together with the high-resolution photographs of the frescos in the church. The various fragments from different sources would then be fitted together.

The first attempts at projection at the church itself were focused on testing the colour quality of the projection onto the irregular and ochre-coloured surface of the apse walls, something very different from a white screen. The tests were highly successful on account of the extraordinary colour quality and clarity achieved by the latest generation of projectors that had been chosen for the task. It was also important to ensure that the projected light would not be harmful to the remaining paintings, and that it would be within the recommended levels. In fact, the intensity of the projection is less than that of the interior lighting in the apse.

Current audiovisual projection techniques make it possible to vary the intensity of the projection. This helps achieve the stated aim of not creating a separate display, but rather of visually returning the paintings to their rightful place on the walls by melting the virtual images in a harmonious continuum with the real paintings.

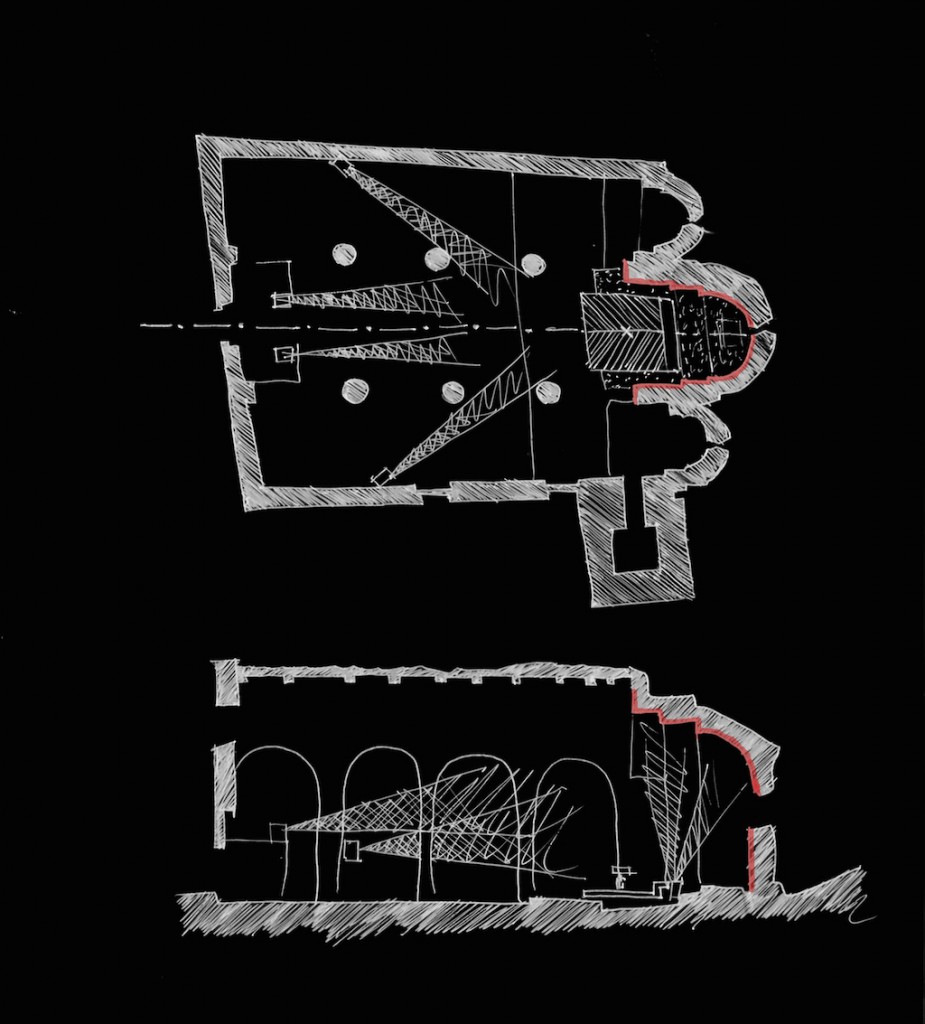

The technical solution for the projection consisted of installing six projectors: two at the church entrance above the reception, two concealed by metal supports in the side aisles, and two in the apse behind the flooring.

This distribution meant that the installation would be practically unseen by visitors. Furthermore, it provided a solution to the problem of projecting onto a complex 3D surface. If projection had been from only one point, the depth of field would not have been sufficient to keep everything in focus between where the presbytery begins and the back of the semi-dome of the apse. Furthermore, this more complete distribution meant the resolution would be improved by a factor of six, making the pixels imperceptible.

Two computers located in the space above the reception complete the projection system by simultaneously transmitting a high-definition signal to the six synchronised projectors.

5. #taull1123

The third stage of the projection consists of a hypothetical reconstruction of what the church would have looked like in 1123, the year it was consecrated. This stage has been popularised through the social media under the name of #taull1123.

From the beginning, it was conceived as being a narrative because, as such, not only would it be possible to emphasise its hypothetical character. It would also make some of the project’s important aspects more readily accessible to the public, such as the art itself and the process of its creation; its formal qualities; its different facets and the various layers and colours that make it up; and the iconography and its significance—and all this done based on the individualisation of the characters portrayed and attention to the most important motifs. The intention was to transmit these ideas without the use of words—not to teach or lecture, but rather to help visitors to see, to transform their gaze, and to help them remember the paintings in their visual memory so they would recognise them in greater and greater detail upon seeing then for a second or third time.

And of course, the idea was to create a propitious atmosphere for creating the impression of travelling back in time and being, for a few moments, next to the artist at the moment of creation. The aim was to let people see the art through the art alone, but with the addition of a touch of magic, too.

It was with this touch of magic in mind that a storyline was devised in collaboration with the MNAC. It went through various phases. At first it had a more historical emphasis; then there was a freer version, and this led to the final version, which focuses strictly on the paintings, shows them in their creation, and uses the necessary lighting techniques to show them in their detail.

The scientific, technical, and artistic process required to reconstruct the original frescos in all their parts was complex. On one hand, it required the digital restoration of all the cracks, missing sections, and gaps in the original, as well as the sometimes quite pronounced marks left by the removal of the original from the walls, as well as the installation of a new apse at the museum with slightly different dimensions. On the other hand, there was the problem of recovering the pictorial fragments that had remained on the church walls and had deteriorated. Their colours had to be recovered and their outlines redrawn on the basis of studies of, and comparisons with, other fragments that had been better preserved. Finally, there was the problem of recreating sections of the paintings that were completely lost. Romanesque painting in general, and that of the apse in the church of Sant Climent in particular, follow patterns with precise rhythms and measurements, and this made it easier to tackle the reconstruction of these sections with a sound footing. Studies of the general geometry, the borders, background colours, and the architectural and decorative elements have made a detailed reconstruction possible.

An analysis of small extant fragments on the walls has, in some cases, led to new figurative hypotheses, especially in the triumphal arches where the figures of the angels holding a shield in their hands have been delineated for the first time.

Moreover, generating the animation required each layer of the paintings to be broken down. This was especially true of the central figure of Christ, which had to be painted again, layer by layer, to create this effect.

The soundtrack for the video mapping was also created according to the same principles and working methods as the rest of the project—that is to say, the combination of scientific restoration with contemporary creativity.

Recordings were made of the sounds of the valley and of the church, as well as of music produced by various mediaeval instruments such as fiddles, flutes, and psalteries. These recordings were then processed to create a digital instrument, the sound of which could be modified while maintaining the character of the instruments. A score was written that, while contemporary, preserves a mediaeval timbre and atmosphere. In large measure, this is responsible for the heightened levels of expression and emotion that the projection conveys.

At the museum and at the church, we can see different aspects of the same thing, different ways of reading an artistic masterpiece, all of which are complementary. At the MNAC, constant museographical efforts have made the original work more accessible in all its splendour. At the church of Sant Climent, contemporary technology, virtual reality, has enabled the blurring of the distinction between original work and its replica by incorporating a new element, time, which provides space for both of them. Visitors can observe what is the real substance of the church and can also see everything that has been preserved in its original location. They can let themselves be carried away by the magic of time travel to see the church as it was in the twelfth century.

The journey back from the past is wonderfully conceived. Little by little, yellow hues of candlelight give way to a colder, contemporary light that still shows the paintings in the vivid colours they had the day they were painted. But the storyline has a twist in store for visitors as a beam of light scans the walls, revealing the reality behind the fantasy by showing what there really is behind every scene: some parts are complete, and sometimes there are only lines and colours. The beam of light broadens its focus, and as it grows in size it erases the projected illusion and returns us to a present in which the significance of each fragment is recorded in everyone’s memory.

Acknowledgements

Ministry of Culture of the Government of Catalonia and “la Caixa” Foundation

In collaboration with: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

General project

Eva Tarrida i Sugrañes, Architect

Eduard Riu-Barrera, Archaeologist

Albert Sierra i Reguera, Historian

Pere Rovira i Pons, Restorator

Jordi Camps i Sòria, Conservator

Audiovisual project

Burzon-Comenge. Albert Burzon

Playmodes. Eloi Maduell

Romanesque paintings restoration

Krom. Mercè Marquès

Lighting

Haz Luz 17. Toño Saiz

Photo and video documentation

Calidos. Maria and Josep Giribet

Architectural project collaborator

Montserrat Cucurella Jorba

Owner and management of the temple

Bisbat d’Urgell and Consorci del Patrimoni de la Vall de Boí

The working process can be followed in detail on the following websites: http://www.romanicobert.cat/taull1123 and http://www.pantocrator.cat.

References

Balcells, A. (ed.). (2003). Puig i Cadafalch i la Catalunya contemporània. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans.

Granell, E., & A. Ramon. (2006). Lluís Domènech i Montaner, viatges per l’arquitectura romànica. Barcelona: Ed. Col·legi d’Arquitectes.

Guardia, M., J. Camps, & I. Lorés. (1993). La descoberta de la pintura mural romànica catalana. La col·lecció de reproduccions del MNAC. Barcelona. MNAC.

Riu-Barrera, E., & C. Payàs. (2000). “La reproducció de la pintura mural romànica de Sant Joan de Boí.” In Boí, Burgal, Pedret, Taüll: Imitació o interpretació contemporània de la pintura mural romànica catalana: I taula rodona. Barcelona: Amics de l’Art Romànic, 31–52.

Cite as:

. "#Taull1123: Immersive experience in a World Heritage Site (or augmented reality without devices)." MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015. Published January 31, 2015. Consulted .

https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/taull1123-immersive-experience-in-a-world-heritage-site-or-augmented-reality-without-devices/