Bring it on: Ensuring the success of BYOD programming in the museum environment

Scott Sayre, Corning Museum of Glass, USA

Abstract

BYOD, or Bring Your Own Device, is a growing rallying cry in business and educational organizations, encouraging or requiring employees and students to provide their own technology. Museums uniquely have two opportunities to apply this approach: one with their staff and the other with visitors. While much has been written in business regarding the IT strategies, policies, and protocols for BYOD implementation in managing employees' devices, very little formal research exists regarding factors leading to successful BYOD museum-visitor programming. In 2012, the Corning Museum of Glass (CMoG) broke ground for its new North Wing Contemporary galleries. Using the new North Wing as a testing ground, the museum began work on a campus-wide digital media strategy for interpretation and museum information management. A core component of this strategy is BYOD, connecting CMoG visitors at a personal level to a range of rich, interpretive content on their personal devices. Understanding there were a number of known and unknown obstacles, the museum developed a cohesive, cross-institutional approach to identify and address each challenge and assure the program's success. This paper provides an overview of preliminary research findings and practices being developed around visitor-focused BYOD at CMoG.Keywords: BYOD, Mobile, Interpretation, Research, Personal Devices, Infrastructure

1. Introduction

In the spring of 2015, the Corning Museum of Glass (CMoG) opened its new Contemporary Art + Design wing, based around a cohesive interpretive strategy focused on “Current Conversations in Contemporary Glass” as an interpretive goal (figure 1). Central to this strategy is the use of digital tools and resources to engage the visitor in new ways for the museum.

In designing this program, CMoG considered the demands of its seasonal audience, with peak days serving upwards of five thousand national and international visitors. To address these needs, the museum internally developed a highly scalable digital environment focused primarily on delivering rich, interactive content to visitors’ personal devices (smartphones, tablets, etc.), as well as fixed media installations for those visitors without their own device. Understanding that historically museums’ Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) programs have met with limited take up, CMoG staff examined common points of failure and the requirements to overcome each point to assure the highest possible usage and visitor satisfaction.

2. Museums and BYOD

BYOD in museums has a checkered past, influenced by both policy and the slow emergence of supporting technologies. Initial policies restricting the use of personal devices in museums were based primarily around the increasing popularity of cell phones in the early 2000s and the perception that their use was disrupting the museum experience. The emergence of the in-phone camera a few years later further challenged museums trying to restrict photography in their galleries. By 2004 many museums had formal or informal rules in place regarding cell phone use in galleries. At the same time, it was common for museums to provide audio-tour devices to their visitors.

The transition to BYOD in museums began in 2005 with two disruptive projects. The first project, by a group of students from Marymount Manhattan College calling themselves Art Mobs (http://mod.blogs.com/art_mobs/2004/11/), produced an alternative audio tour for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City as a downloadable podcast. The project encouraged museum visitors to preload the podcast onto their personal iPods and bring them to the museum. MoMA was quick to respond and take full advantage of this idea, producing its own audio tour podcasts. The second project was Walker Art Center’s Art on Call, which delivered an interactive audio tour through visitors’ personal cell phones. Both of these projects sought to encourage visitors to use their own personal devices, from MP3 players to cell phones, to enhance their museum experience (Sayre & Dowden, 2007). Visitors’ BYOD capabilities took a tremendous leap forward with the release of Apple’s iPhone and iPod touch in 2007 and the plethora of smartphones and tablets that followed.

Outside museum walls, the popularity of smartphones has grown to over two-thirds of consumers owning one (Kelly, 2014). The proliferation of personal mobile devices has impacted business and educational organizations by encouraging or requiring employees and students to provide their own technology (Willis, 2014). This sea change, along with the emergence of mobile apps, responsive Web design, and social media, provides new opportunities for museums like CMoG to move away from providing hardware to its visitors and adopt a BYOD approach. In order to take full advantage of getting out of the business of providing visitors with devices, museums need to make a concerted effort to identify and control the many variables leading to the personal and social engagement of visitors through their own devices.

3. Harnessing the opportunity

In assessing BYOD as a solution, CMOG reflected on the past decade of discovery, research, and technology changes related to museum BYOD. From this assessment, the museum determined that the external environment (visitor comfort and technology) was mature enough to proceed, but then faced the complex challenge of identifying and addressing the many internal variables that would ultimately impact the program’s success (Johnson et al., 2013).

Organizational convenience versus commitment

After a couple of decades of providing audio-tour equipment, having visitors provide their own equipment looks like a godsend to most museums. No longer do museums have to rent or purchase equipment, dedicate space for its storage, keep the equipment charged and in good repair, update and maintain content and software, and train and pay staff to support it and secure it. On the surface, all the museum needs to do is produce good content (not an easy task by any stretch) and market the programs availability. In actuality, this apparent convenience actually opens the door to a more complex set of challenges, as well as some exciting new opportunities. CMoG knew going in that in order for the new BYOD program to be a success, the entire organization would need to commit to addressing every challenge.

4. BYOD variables for success

The success of a BYOD program can be looked at as a systems approach to a series of interdependent interactions between the visitor and the museum staff, environment, and content. All defined variables for success impose some degree of responsibility on both the museum and the visitor. In most cases, the museum is capable of facilitating the engagement of the visitor, but is not in complete control of the outcome. Through past experience, visitor feedback, and experience of other museums, CMoG used a process based on Stanford University’s design thinking to envision and hone the BYOD visitor experience. Institution-specific visitor/user scenarios were developed and resulted in eight related variables that could significantly impact the overall success of a BYOD program:

- Awareness

- Access

- Compatibility

- User capability

- Supporting amenities

- User interest

- Usability

- Impact

Success variable 1

Awareness

Visitor awareness of the availability of a BYOD program is by far the most critical, but often overlooked, component of a successful program. Until recently, museum visitors expected to see racks of audio-guide hardware as well as signage when a mobile tour was available. Along with this, front-line staff was required to not only distribute, but also promote the program in order for it to pay for itself. Beyond the initial handoff, visitors committed to visibly carry traditional audio-tour hardware throughout their visits, ultimately marketing the program’s availability to visitors who may have missed or neglected to get a device upon entry.

Alternatively, the availability of BYOD programming, be it cellphone audio or rich media application, is completely invisible to visitors unless the museum makes a concerted effort to promote it and provide the means to access it throughout the visitor’s interaction with the museum.

CMoG’s approach

Ideally, visitors would be aware that their personal smartphones can be an exciting component of a visit to CMoG in advance of arriving at the museum. While this level of preparedness can by no means be expected, the messaging about BYOD starts as early as possible. The primary vehicle for this messaging is the museum website’s Plan Your Visit section, which markets the program and its contents and encourages visitors to bring their smartphones and headphones and ideally have them fully charged.

A key part of CMoG’s awareness strategy is generating name recognition for the program “GlassApp” and emphasizing that it is free and available at every contact point (figure 2). The goal is for visitors to refer to it by name and see it as a valuable component of a visit to the museum.

For the visitor arriving on site, GlassApp program messaging starts at the museum’s Welcome Center and Admissions lobby, where visitors are reminded to bring their phone and headphones through both printed and digital signage. Signage throughout the museum advertises GlassApp and links it to both general and specific applications. Examples include large video monitors in the contemporary galleries introducing the collection and also inviting the visitors to join the conversation through GlassApp. iPads tethered to benches in the galleries run GlassApp and encourage users to continue their experience on their own smartphones. The interpretive labels for objects covered in the program contain a smartphone/Wi-Fi icon with the name of the app (the same as the Wi-Fi and hashtag). In the museum’s hot-glass theaters, a pre-show digital slideshow informs visitors they can get up-to-the-minute information on everything from the day’s exhibits and programs to the restaurant menu. Awareness is where everything starts when it comes to BYOD; without it, even the best programs won’t succeed.

Success variable 2

Access

Once a visitor is aware of the BYOD program’s existence, the next challenge is for them to access it. Since BYOD programs come in a variety of formats, from cell-phone tours to downloadable native apps, the visitor must not only understand how to access the program, but be in a place where they have the technical capability. Unless a museum expects its visitors to download a podcast or app in advance, the museum must provide a reliable technological infrastructure to support access once a visitor arrives at the museum. Unfortunately, museum galleries, often because of unique building architecture, are notoriously difficult to broadcast or receive cellphone signals in. For many museums, providing robust museum-wide wireless service requires a major financial investment in hardware, installation, and services. Institutions delivering externally hosted content also have to assure that they have the external bandwidth to support high simultaneous network demands from both staff and BYOD visitors. Ideally, access to museum BYOD programming for the visitor should happen as seamlessly and painlessly as possible. Over 70 percent of visitors have Wi-Fi in their homes and are used to a high level of wireless service, raising expectations for museums, particularly when visitors are using their own personal devices.

CMoG’s approach

CMoG had been providing limited free public Wi-Fi to its visitors for a few years prior to the new BYOD initiative. Service had suffered from limited coverage and bandwidth and minimal marketing. Museum visitors were also challenged by the visibility of numerous private and dedicated access points serving the corporate office buildings next door, as well as specific functional areas of the museum. Cell-phone coverage was also spotty in many of the galleries due to the construction of the buildings, as well as the hilly region in which the museum is located.

Understanding the importance of access to the success of its BYOD initiative, the museum made a major investment (more than $250,000) in infrastructure, as well as a directed effort to clearly identify and isolate the Wi-Fi dedicated to BYOD.

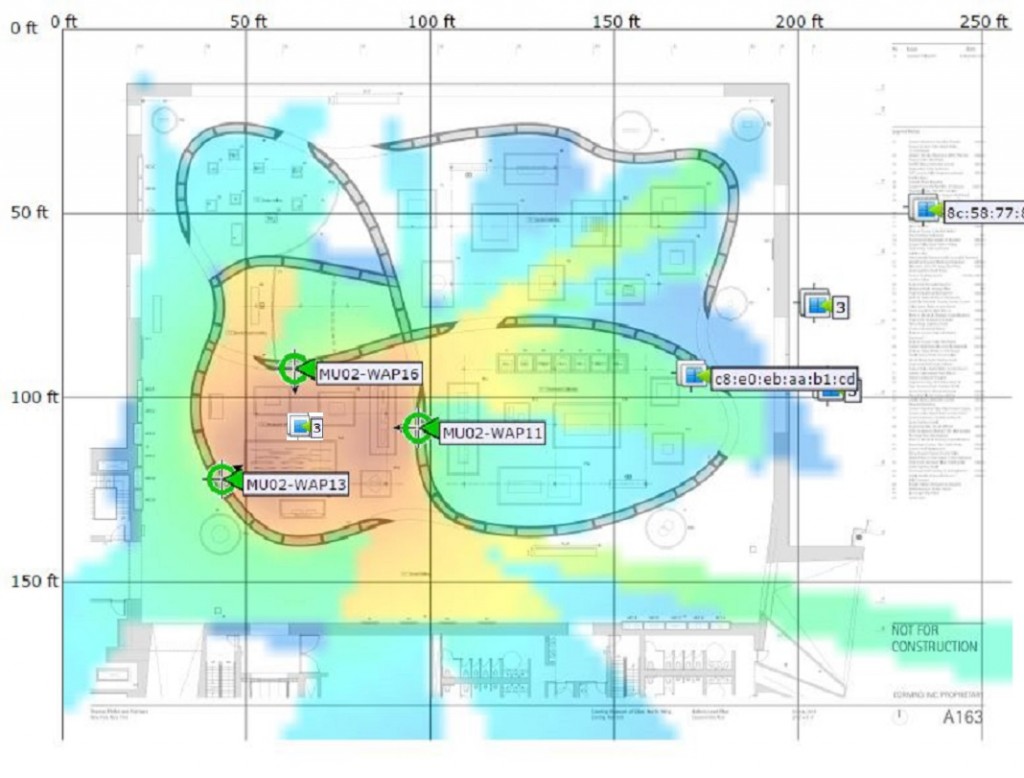

Starting with the museum’s newest Contemporary Art + Design wing, CMoG installed an all-optical multifunction fiber network called Corning One, which both delivers high-speed Wi-Fi and relays external cellular services into the galleries, admissions, and other public spaces. Each public space was heat-mapped to determine access-point requirements and placement for comprehensive coverage (see figure 3). All access points were set to broadcast one visible SSID named GlassApp to make it easy for visitors to identify the network. Museum IT staff worked to hide the SSIDs of all the other internal networks and worked with the neighboring buildings to minimize spillover. The GlassApp Wi-Fi network was configured to push a Wi-Fi log-in page to all visitors with their Wi-Fi turned on. The log-in page was designed to require no authentication other than a button to “Start GlassApp,” which takes the visitor to main menu of the BYOD Web app (more on this later).

CMoG decided that the simplest way to combine its efforts in awareness with access was to push visitors to log onto the GlassApp Wi-Fi rather than a specific URL. The GlassApp internal domain, subdomain, and sub-directory were also configured to help catch visitors who get lost or leave GlassApp. Links to GlassApp were also added to the museum’s primary website and mobile site.

Success variable 3

Compatibility

When it comes to compatibility of BYOD programming with visitor’s devices, museums have the choice of creating native apps or Web apps. While native apps have some advantages when it comes to advanced functionality, on-board content (not requiring an internet collection), and better operating system integration, they are more complex to produce and maintain, particularly when producing and supporting multiple versions of a native app, different versions of the operating systems (iOS, Android, Windows, etc.), and different formats (smartphones, tablets, etc.). Native apps also need to be downloaded, installed, and updated by users, creating potential for issues of incompatibility over time. Alternatively, today’s Web apps can provide a comparable interactive user experience and are much simpler to develop and easier to maintain (Forbes, 2011). Neilson (2012) explains:

Apps may remain better for tasks that are intensely feature-rich applications, such as photo editing—whereas mobile sites will be better for design problems like e-commerce/m-commerce, corporate Websites, news, medical info, social networking, etc. that are rich in content but don’t require intense data manipulation.

Web apps play in a browser and are based around Web standards shared among different mobile operating systems, making them widely compatible. From the visitor’s perspective, accessing a Web app is as simple as clicking on a text link, rather than going to the additional step of downloading and installing an app. Web apps’ two greatest weaknesses are that 1) they are reliant on an active network connection in order to fully function, and 2) they currently have limitations when it comes to accessing device-specific hardware such as Bluetooth (required for BLE beacons) and integrated cameras.

CMoG’s approach

After weighing the pros and cons of native versus Web apps, CMoG decided to develop GlassApp as a responsive client-side Web app based on the following criteria:

- Because a Web app is browser based and delivered on demand, the visitor can use GlassApp instantly without any transaction and always accesses the latest version of the app.

- A large percentage of CMoG visitors are international tourists using a wide range of mobile platforms, some of which are less common in the United States, making it harder to cover all potential platforms with native apps.

- CMoG has the Wi-Fi infrastructure to support a high-quality constant network connection for all visitors with wireless devices.

- CMoG needed GlassApp to be compatible with a wide range of screen sizes, from smartphones to tablets. Beyond being available on visitors’ phones, the program is being used by docents with iPads and is also available on iPads tethered to benches so visitors without phones can access the program. Responsive Web apps like GlassApp can automatically adjust to different screen sizes and viewing modes (portrait versus landscape).

- The internal digital media team could more easily develop, revise, support, and maintain a Web app and integrate it with other core systems through the Drupal content management system used to manage the museum’s main website.

Web apps also offer the option of publishing the same program as native apps, using tools like Apache Cordova or Adobe PhoneGap, which is not currently in the museum’s plans. This makes it possible to pilot-test or publicly release versions of GlassApp with native app functionality instead of, or in addition to, the Web app.

Success variable 4

User capability

Assessing users’ capability with their devices can be challenging since the bar is ever changing with equipment and social norms. This is further complicated by generational and cultural differences. Where a teen might not “do email,” a senior might not text, let alone know whether their device has Bluetooth and if it is enabled (Thompson, 2014). International visitors might have cellular capabilities, but choose not to use them due to issues with compatibility or cost. At a basic level, capability is limited by compatibility, but users with limited technical capability often don’t understand the difference between their own capabilities and that of their personal devices. Museums are limited in their ability to impact a visitor’s technical virtuosity. While access to quality content is an incentive, the time and social constraints of a museum visit can be limiting. With this in mind, museum BYOD requirements need to be defined specifically around the capabilities of their target audience(s).

CMoG’s approach

In choosing the Web app approach to BYOD programming, CMOG wanted to provide the lowest barrier to entry possible to assure the majority of the visitors access to the program with little or no intervention from museum staff. One example of this was the decision to use visual browsing organized by object-to-object proximity and full-label text search as the primary means of accessing object information, rather than reliance on QR codes, which the museum found were rarely used in past programs. CMoG’s extreme spikes in seasonal visitation, along with the diversity of visitors, from local teens to international traveling seniors, were key in making this decision to keep the app as simple as possible.

One area of current compromise was in the integration of location services to assist museum visitors in determining their current location and navigating the galleries and campus. The museum’s architecture and campus is complicated and confusing for many visitors. Printed maps are helpful, but small, device-based maps are almost useless and potentially even more confusing due to the small size of the screen and visitors’ inability to locate themselves in the space (“You are here”). Because of this, it was decided that the initial version GlassApp would not include a map, and the museum would wait until location-based technologies like Beacons and Wi-Fi-zone proximity further mature, along with devices that support them. Once these technologies reach the mainstream, visitors will more likely come to the museum with the knowledge and preparation necessary to assure a positive user experience.

Success variable 5

Supporting amenities

As mentioned earlier, museums have not historically been thought of as mobile-friendly environments. This perception has to visibly change in order for visitors to feel both comfortable and supported in bringing and using their own devices. One of the primary visitor concerns in this area, particularly for travelers, is battery charge and usage. A poll of CMoG visitors carrying smartphones showed that 60 percent felt battery usage was a chief concern in using their personal devices to access a BYOD program. Mobile friendly environments like airports and shopping malls provide visitors the means to not only charge their devices, but also purchase additional accessories such as back-up batteries and headphones. CMoG’s survey also showed that less than 20 percent of visitors with smartphones brought headsets with them, while many expressed a concern about listening to audio in the galleries (Sayre, 2015). Museums implementing BYOD programs need to consider how to address these issues by selling, loaning, or renting headsets. The airline-movie model of loaning or giving away inexpensive headsets could be one possible solution.

Museum staff’s familiarity with the program is another amenity critical to the success of a museum BYOD experience. Staff knowledge of and ability to support the program is not only key to visitor awareness, but also an important component of day-to-day public messaging. In order to offer the best visitor experience possible, staff must understand the capabilities of BYOD in order to also understand how to improve the content and service over time.

CMoG’s approach

As a tourist destination, CMoG is well versed in providing visitor amenities. The museum maintains a customer-service rating greater than 95 percent and sees meeting visitor needs as primary to the museum’s growth and success (D.P. Research Solutions, 2015). While BYOD was identified as the best workable solution for meeting visitor needs, the museum understood it had shortcomings when it came to embracing and supporting visitors with their own devices.

CMoG first identified the need to provide public access to power. CMoG embraced the idea of providing charging stations as an ubiquitous amenity like bathrooms and drinking fountains. A survey was done of the campus, identifying locations where visitors naturally congregate or wait. The intent was to be proactive in installing charging stations in places where both the museum and the visitors would find benefit. Locations included the museum’s café, lobby, motorcoach waiting area, auditoriums, and glassmaking waiting areas. The charging stations offer both AC and high-power (15 amp) USB outlets to help charge devices safely and quickly. Signage was developed to identify both the charging station and the availability of GlassApp over the free Wi-Fi.

Beyond charging, the CMOG shops identified a range of mobile accessories to both support and enhance the visitor’s BYOD experience, from battery packs to headset splitters. These products have their own dedicated area in the CMoG shops, with some also available as point-of-purchase items at admissions and information desks. The museum is also considering loaning headsets left over from previous audio tour initiatives.

Lastly, and most importantly, CMoG’s administration felt it was critical for all staff to be trained on the BYOD program and to understand how to access, use, and support it and gather useful feedback on improving it. CMoG’s Human Resource department included the GlassApp as a mandatory training session in all staff’s annual professional development program.

Success variable 6

User interest

Awareness and interest are intertwined, like hearing and listening. Successful programs play on theses subtleties. Unlike ATMs, for which there is intrinsic user motivation based on a known and valued outcome, museum mobile tours are a mixed bag. Most museum-seasoned visitors have experienced the extremes of mobile interpretation, from the boring and disconnected to the engaging and highly informative. Unlike programs delivered on museum-provided devices, which visitors often commit to at the beginning of a visit, BYOD program use tends to be more spontaneous, with the visitor being motivated enough to get out the device, often hidden in a pocket or purse, and make use of it. The more museums can to do help visitors understand and appreciate the potential value of a BYOD program the more likely visitors are to access it—at least once.

CMoG’s approach

The museum saw generating interest in the program as a real tipping point for convincing visitors to make use of the BYOD GlassApp program. Because of this, a great deal of effort was placed on exposing the content and experience to visitors through other media channels. A primary vehicle for this messaging is video “trailers” or previews that give the visitors a peak into GlassApp content and invite them to engage.

Two 65-inch HD monitors are installed in the new Contemporary Art + Design wing that feature a video of the contemporary art curator introducing the visitors to the building and collection, as well as highlighting some of the video segments in GlassApp. The curator also invites the visitor to join the conversation through the hashtags (#glassapp and #newspacenewlight) and social media channels connected to the exhibit. A section of each monitor is dedicated to a live aggregated feed of GlassApp-related posts by visitors to reveal the conversation.

Elsewhere in the museum, video screens in hot-glass theaters show trailers for the GlassApp between performances, inviting visitors to log on and join the conversation. Museum docents are trained on GlassApp and integrate components of it into their tours. Docents are also encouraged to invite the visitors on a tour to continue the experience using GlassApp after the tour. Together, these techniques for revealing the content of GlassApp are designed to move the visitor from awareness to action, logging on to explore what GlassApp has to offer.

Success variable 7

Usability

Once a visitor has made the investment to get out his or her device, log in to the Wi-Fi, and launch a Web app, the program’s design, interface, and responsiveness needs to be fluid and intuitive. Museum Web developers have been actively conducting usability testing for well over a decade to assess ease of use of websites. These same techniques have been carried forward to the development of native apps and now Web apps. While native apps were previously considered more usable, recent developments in responsive HTML5, JavaScript, and CSS frameworks have improved the potential Web app user experience enough to compete with, if not exceed, the usability of native apps (Neilson, 2014). In order to take full advantage of these new Web technologies, museums need to thoroughly define their intended user experience through use case scenarios, test against defined objectives with real users, and revise the application design until the intended experience and expectations of the user are achieved.

CMoG’s approach

CMoG’s administration and digital media team went into the project committed to iteratively developing, testing, and improving the GlassApp application over its lifetime. The program’s tight initial development cycle, building construction schedule, and necessary release prior to peak season limited the staff’s ability to do extensive testing prior to the initial release of GlassApp. Numerous wireframes and interactive prototypes were built, reviewed by staff, and revised early in the program’s development. Lessons learned from past CMoG mobile sites as well as best practices from other museum apps were also used to inform the design of the initial release. CMoG digital media staff had to accept the fact that they would not be able to fully test GlassApp until peak season begins in the spring of 2015, since the demographic of winter visitors is local and significantly different from the tourist audience, which makes up a significant proportion of the museum’s visitation.

Success variable 8

Impact

In the best-case scenario, the visitor has made it to the point of being able to consume and pass judgment on the value of the content within a BYOD program. The visitor has made a significant commitment to get this far, and hopefully it will pay off for them. From the museum’s side of the story, this is where the real challenge begins—producing truly valuable, engaging content. While educational pedagogy and philosophy are beyond the scope of this paper, this is the critical point where they truly come into play. Engaged visitors will test the content’s value, and if they are engaged, they may continue to delve deeper; if they are not, their phones will go back in their pockets or purses, and the system’s approach comes to a dead end.

We are all familiar with good and bad content. We share podcasts, websites, and videos that have universal appeal and quickly dismiss those that fall short. In the end, it’s the quality of the BYOD content that will be put to the test in the minds of our visitors. Let’s face it: it’s a tall order.

CMOG’s approach

The BYOD GlassApp is part of a large, museum-wide interpretive initiative that focuses on the development of visitor-centered interpretive materials ranging from interpretive object labels and docent tours to live demonstrations and interactive digital media. These interpretive threads were defined and developed together as an overarching system, to reduce redundancy and connect with the visitor at a personal level.

GlassApp’s approach to content and visitor engagement is based around a conversational format. Each object is explored through a short one- to two-minute video conversation between an actor playing an interested visitor and a wide range of museum staff. The conversations are unscripted and designed to feel both authentic and natural, intended to lower the barrier between the objects and the visitor. An integrated social-media section illuminates related visitor conversations on a range of social media channels and invites the user/visitor to join in.

Writing and content development is based around the “If you can’t see it, don’t say it” model (Wetterlund, 2013). Cross-departmental teams of staff from curatorial, education, digital media, the museum’s Rakow library, and the hot-glass theaters were trained on this interpretive approach and worked together to develop, edit, and approve all of the interpretive content in GlassApp and in galleries. The interpretive approach was also informed by popular media programs ranging from RadioLab and Garrison Keillor’s Writers Almanac (biographies) to Portland Art Museum’s Conversations about Works of Art and Baltimore Museum of Art’s Go Mobile. CMoG staff felt this merger of proven interpretive practices mixed with popular cultural-programming models would result in the best impact, engagement, and extended interests of CMoG’s diverse audience.

5. A future iterative practice

The BYOD GlassApp is only one component in the test-bed phase of a museum-wide interpretive plan to reimagine the museum’s collections and programs based on an integrated, visitor-centered approach. The GlassApp application and supporting back-end systems are designed to be flexible, making it easy to expand and, more important, to modify the program over time. With the program itself, the variables defined in the current systems approach will likely change with our visitors, the technology, and our own discoveries. The museum is investing not only in the development of new content around a new interpretive strategy, but also in the ongoing assessment of and response to the visitor effectiveness of the approach. This institutional commitment provides for a dynamic, iterative practice for the ongoing improvement of content, tools, and techniques as the program is expanded to address the entire collection over the next five years. We look forward to continuing learn from others and ourselves as we share our discoveries along way.

References

ArtMobs. (2004). Art Mobs Launches on Dec. 8! Available http://mod.blogs.com/art_mobs/2004/11/

Baltimore Museum of Art. (n.d.). BMA GoMobile. Available http://gomobileartbma.org/

D.P. Research Solutions. (2015). Visitor Satisfaction Survey. A private report prepared for the Corning Museum of Glass. The Corning Museum of Glass.

Forbes, T. (2011). Native or Not? Why a Mobile Web App Might Be Right for Your Museum, Mobile Apps for Museums, American Association of Museums.

Johnson, L., S. Adams Becker, & A. Freeman. (2013). BYOD, The NMC Horizon Report: 2013 Museum Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium, 11

Kelly, S. (2014). “Two-thirds of U.S. Consumers Own Smartphones.” Mashable. February 13, 2014. Available http://mashable.com/2014/02/13/smartphone-us-adoption/

Lewis, A. (2014). What’s it like for Museum visitors to connect to Wi-Fi on a mobile phone? V&A. May 6. Available http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/digital-media/mobile-wifi-screens

Mir, R. (2014). Museums Share Their Best Practices for Reaching Multilingual Audiences. Guggenheim Blogs. April 25. Available http://blogs.guggenheim.org/checklist/museums-share-their-best-practices-for-reaching-multilingual-audiences/

Neilson, J. (2012). Mobile Sites vs. Apps: The Coming Strategy Shift. Nielsen Norman Group. February 13. Available http://www.nngroup.com/articles/mobile-sites-vs-apps-strategy-shift/

Neilson, J. (2014). Responsive Web Design (RWD) and User Experience. Nielsen Norman Group. May 4. Available http://www.nngroup.com/articles/responsive-web-design-definition/

Pew Internet Project. (2013). Broadband Technology Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center. Available http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/broadband-technology-fact-sheet/

Proctor, N. (2009). BYOD and the Museums Interpretive Mission, MuseumMobile Wiki. Available http://wiki.museummobile.info/archives/142

Radio Lab. (n.d.). New York Public Radio. Available http://www.radiolab.org/

Sayre, S. (2015). CMoG Smartphone Survey, unpublished survey conducted by the Corning Museum of Glass.

Sayre, S., & R. Dowden. (2007). The Whole World in Their Hands: The Promise and Peril of Visitor Provided Mobile Devices, The Digital Museum: A Think Guide, American Association of Museums.

Stanford University. (n.d.). Welcome to the virtual crash course in design thinking. Available http://dschool.stanford.edu/dgift/

Thompson, D. (2014). iBeacon: Is Bluetooth On? And Other Insights from Empatika. BEEKn. Available http://beekn.net/2014/03/ibeacon-bluetooth-insights-empatika/

Wetterlund, K. (2013). If you can’t see it, don’t say it – A Guide to Interpretive Writing About Art for Museum Educators, Museum-Ed. Available http://museum-ed.org/a-guide-to-interpretive-writing-about-art-for-museum-educators/

Willis, D. (2014). Bring Your Own Device: The Results and the Future, Gartner Research. May 5. Available https://www.gartner.com/doc/2730217?ref=SiteSearch&sthkw=BYOD&fnl=search&srcId=1-3478922254#a-2130447389

Writer’s Almanac with Garrison Keilor, The. (n.d.). Today is the birthday of… American Public Media. Available http://writersalmanac.org/

Cite as:

. "Bring it on: Ensuring the success of BYOD programming in the museum environment." MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015. Published January 31, 2015. Consulted .

https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/bring-it-on-ensuring-the-success-of-byod-programming-in-the-museum-environment/